The Paris 2024 Olympics Opening Ceremony was remarkable in its scale. Rather than constricting the events to a stadium, as had been the case since Athens hosted the first iteration of the modern games in 1896, Thomas Jolly and his team sought to transform Paris itself into a stage. From Lady Gaga’s cabaret act on the banks of the Seine to Celine Dion’s closing number on the Eiffel Tower, each performance paid homage to Paris’s longstanding reputation as a city of spectacles—whether they be political (decapitating royalty), social (barricades taking the streets), or cultural (models strutting down runways). But one spectacle overshadowed them all: the lighting of the Olympic Cauldron. Under a pestering rain, Marie-José Pérec and Teddy Riner, French Olympic legends, lowered their torches onto a metal ring that lit up. As the camera panned out, it revealed a silver balloon that raised the Cauldron above the Jardin des Tuileries—a spectacle intensified by the Eiffel Tower’s shining presence in the background.

The Olympic balloon’s success surpassed the organizers’ expectations. The 100,000 free tickets to see it up close were fully booked almost as soon as they were made available. Even larger numbers flocked to areas surrounding the Louvre and viewpoints in Montmartre to watch it ascend each evening. While the balloon was grounded after the Olympics closing ceremony, it reascended on 28 August to celebrate the opening of the Paralympic Games and will remain a presence in the Parisian sky at least until they conclude (the additional 100,000 tickets made available to visit it were also quickly claimed). In the meantime, a growing movement is calling for the floating globe to become a permanent fixture in the city (supporters include the mayor, Anne Hidalgo).

Commentary about the Olympic balloon following the Opening Ceremony was quick to reference the technology’s French origins. On 4 June 1783, two brothers—Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier—made the first demonstration of a hot-air balloon in Annonay, a town in southeastern France. However, that episode was just the beginning of France’s rich aeronautical history, and it does not explain why balloons and Paris seem to go together like brie and baguette. Rather than a new element in the Parisian skyline, the Olympic balloon is more akin to the rediscovery of an old icon.

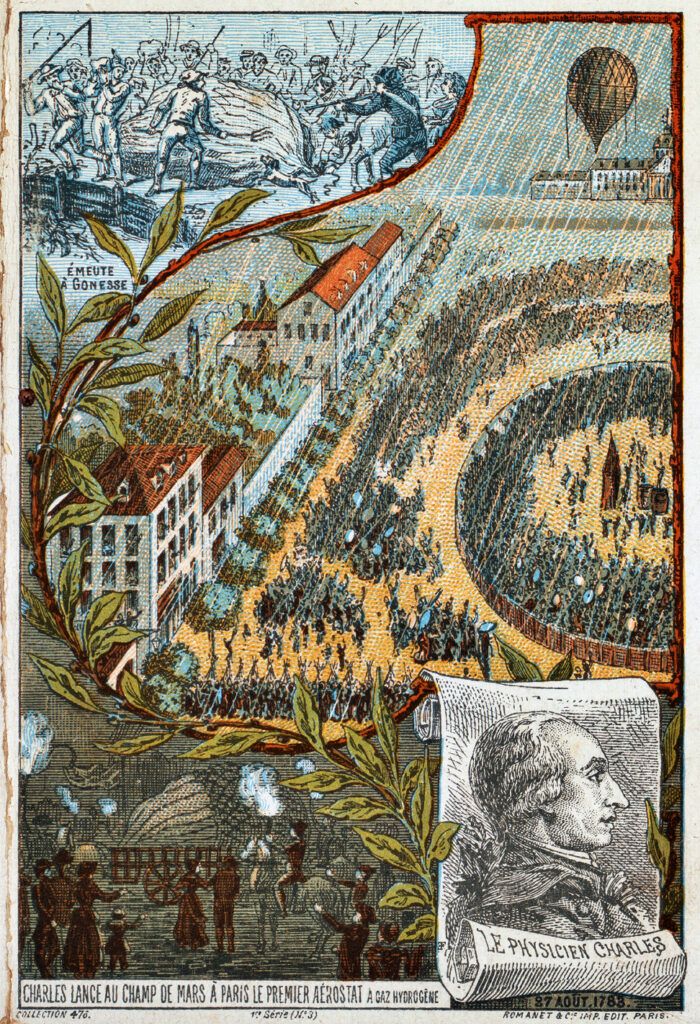

The first thing to clarify is that the Olympic balloon is not a hot-air balloon, but a gas balloon. Rather than rising by heating the air inside the open envelope, it ascends thanks to helium inside the sealed envelope. While today the Montgolfier name is etched in history (a hot-air balloon is also known as a montgolfière), we would be remiss not to recall the inventor of the gas balloon. At around the same time, Jacques-Alexandre Charles was experimenting with what was then called “flammable air” (another Frenchman, Antoine Lavoisier, would go on to coin the term “hydrogen”). Charles organized his own gas balloon experiment and, on 27 August 1783, hundreds of thousands of Parisians witnessed the charlière depart from the Champ-de-Mars.

Among those witnesses was Benjamin Franklin, who, after hearing someone mock the apparatus, supposedly quipped: “Eh! What is the use of a newborn baby?” Franklin’s point was that while the floating globe seemed silly, it would develop into something practical. In the ensuing decades, finding some kind of use for balloons became a French obsession. The Académie des Sciences researched ways to steer them against the wind, while the army used them for aerial observations during the warfare that followed the 1789 French Revolution.

However, by the mid-1800s, there was a sense of disillusionment with the technology. The entry for “Ballooning” in the 1860 edition of the Dictionnaire des inventions et découvertes anciennes et modernes disappointedly stated that “the art of aerial navigation had not progressed at all” since the balloon’s invention. Instead, the practice had fallen into the hands of entertainers and speculators who toured Europe and the Americas trying to make a quick buck through frivolous ascents.

So, why is it that we now associate balloons with the City of Light? The answer lies with the ballooning revival France experienced in the late nineteenth century. The turning point was the 1870-1871 Franco-Prussian War. A series of defeats in the early days of the war produced the fall of the Second Empire, which had been headed by Napoléon Bonaparte’s nephew since 1851. The authoritarian regime was replaced by the Third Republic, which modeled itself after the ideals of the French Revolution. Rather than surrender, the new leadership chose to frame its battle against Prussia as an existential defense of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

But France was woefully unprepared and experienced a traumatic defeat. Contemporaries identified few saving graces from the war, the main one being the resistance Paris mounted to a four-month long Prussian siege. In a turn of events that seemed more appropriate to a Jules Verne novel, Parisians adopted an ingenious method to communicate with the world beyond their city’s walls. Throughout the siege, more than sixty balloons—about one every other day—departed Paris carrying mail, special cargo, and even politicians. Parisians developed a fondness for this whimsical system that transported more than 1.5 million letters. “It seems to me that this aerial messenger carries away a part of myself,” a journalist wrote.

Because the adoption of balloons coincided with the establishment of the regime, the technology acquired a new kind of political legitimacy. Léon Gambetta, a prominent republican leader, escaped the city by balloon to organize the war effort in the provinces—an episode that French schoolchildren would go on to learn by heart. In the years that followed, a thriving scientific community that adopted balloons for atmospheric investigations coalesced in Paris. Its members deliberately associated their aeronautical practices as a service to the Third Republic, arguing that mastering the air was necessary if the fledgling regime was to hold its own against the German army and British navy. In 1875, when two aeronauts died of oxygen deprivation during an 8,500-meter-high ascent, the French compared them to soldiers who had given their lives to France during the Franco-Prussian War and memorialized them as the Third Republic’s first scientific martyrs.

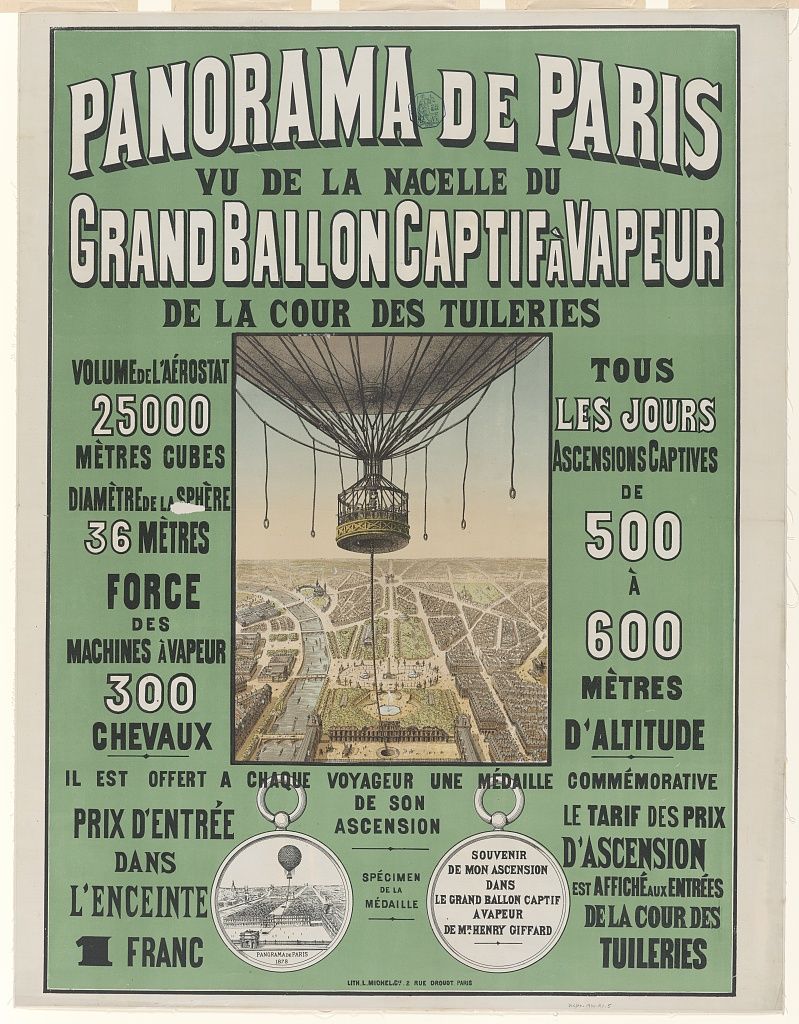

All the while, the balloon had become a staple in the Expositions Universelles—nineteenth century mega-events that prefigured the modern Olympics. The French organized no fewer than five between 1855 and 1900. In 1867 and 1878, the millions of visitors who came to Paris amused themselves by going up in giant tethered balloons designed by Henri Giffard and looking down the new boulevards being pierced by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Just like the Olympic balloon, Giffard’s 1878 balloon operated from the Jardin des Tuileries, although it was much larger (36 meters wide by 55 meters tall vs. 22 meters wide by 30 meters tall) and rose quite a lot higher (five hundred meters vs. sixty meters).

The Giffard balloons were so successful that one could even say they contributed to the creation of the ultimate Parisian monument. In his proposal for a large iron tower, which faced some vociferous opposition, Gustave Eiffel appealed both to its entertainment and scientific potential. Like the 1878 balloon, he explained, the Tower could be both a success with crowds and used for meteorological observations. Tellingly, while the Montgolfier brothers were not among the seventy-two men of science and engineers honored with their names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower, one can find Giffard’s on the South-West side. (It is also worth noting that, like the Olympic balloon, the Eiffel Tower was only supposed to be a temporary addition to the city).

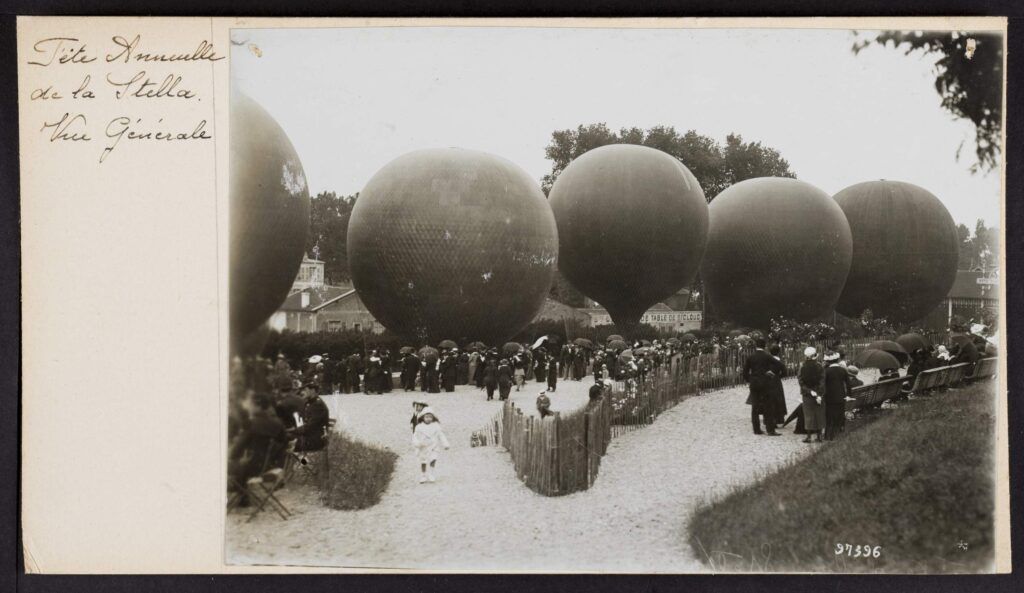

By the turn-of-the-twentieth century, the balloon was no longer an object of mockery, which meant that it could also be appropriated by the higher echelons of French society. In 1898, aristocrats and wealthy bourgeois men came together to form the Aéro-Club de France, an institution that infused ballooning with a distinct fashionable aura. The Aéro-Club would host exclusive parties in Saint-Cloud, a wealthy area in Western Paris, where fancy drinks and glamorous performances were accompanied by spectacular balloon ascents.

During the Belle Époque, a period that has come to define our image of Paris, the city was the indisputable aeronautical capital of the world. Between 1899 and 1910, members of the Aéro-Club alone conducted more than three thousand ascents. The city also hosted the ateliers of skillful manufacturers, like that commanded by Henri Lachambre, which received balloon orders from France and beyond. In addition, with the expansion of the mass press and the advent of photography, people everywhere got to see images of balloons ascending in Paris.

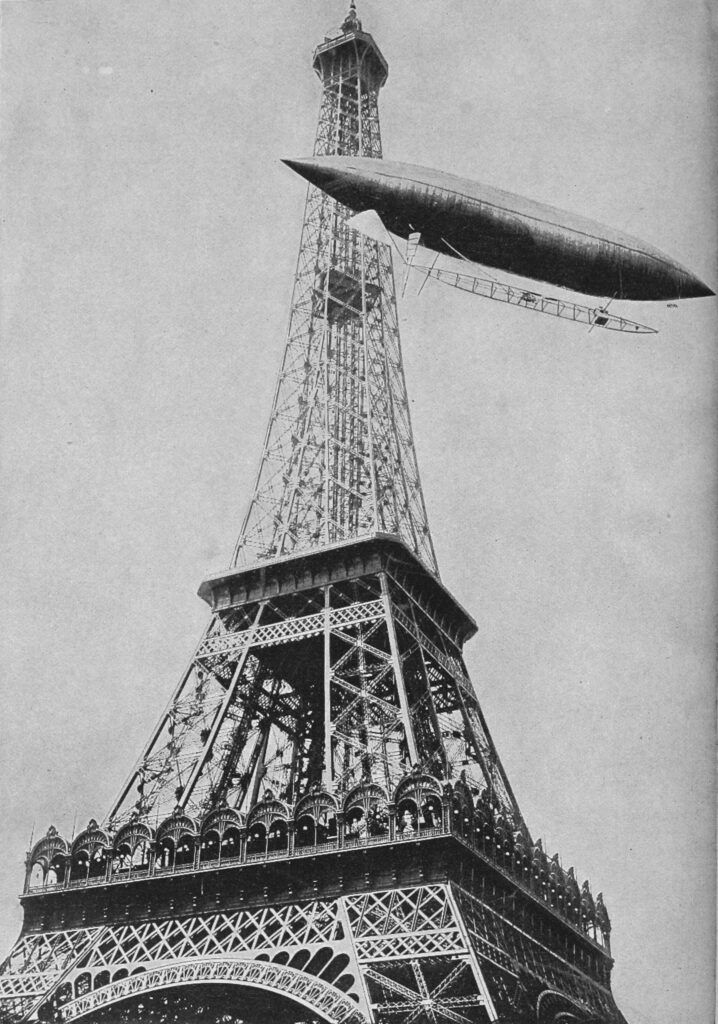

Meanwhile, technological advances in the burgeoning automobile industry enabled the production of more efficient engines that helped transform balloons into airships. The Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont, the first aeronaut to become a global celebrity, regularly flew his airship around the Eiffel Tower, an image that revived people’s hopes that one day humans would be able to steer machines above the clouds.

Making the Olympic balloon a permanent attraction would not only be a whimsical addition to Parisian skyline, but it would also honor the city’s aeronautical past. In fact, the movement’s request is relatively humble given what spectators at Paris’s first Olympic Games got to see. Hosted in conjunction with the 1900 Exposition Universelle, the competitions that year also featured a series of balloon races, and spectators got to see about 150 balloons depart from what one might also call the City of Flight.

Patrick Luiz Sullivan De Oliveira is an Assistant Professor of History at IE University in Madrid, Spain. His book, Ascending Republic: The Ballooning Revival in Nineteenth-Century France, will be out with MIT Press in 2025.