Dr Daniel Gordon is Senior Lecturer in European History at Edge Hill University

On Not Doing Things: Or, It’s Décroissance, Jim – But Not As We Know It!

It is possible that I am the first contributor to this feature to have spent the entirety of the Covid-19 lockdown thus far being, er, ill with suspected Covid-19. In the circumstances I trust I will be forgiven for not having spent the lockdown as the beneficiary of some putative ‘Covid-19 Distinguished Mid-Career Research Fellowship’ burst of academic productivity.

Yet the combination of illness and lockdown has created plenty of time (perhaps too much) for the one activity that modern neoliberal academe normally has little time or space for: thinking. My case has mercifully not been bad enough for overnight hospital admission, and has dragged on so long that I am far past the danger zone. So there have been extended periods when I have had the luxury of my thinking to be things other than ‘Are my muscle spasms starting up today sooner or later than yesterday?’ or ‘Why does French broadcasting’s public service announcement say if you develop symptoms call a doctor at once, but the UK equivalent says pretty much the opposite?’.

Perhaps I could claim to have gone on a crash course in the history of temporality, prompted by the surreal contrast between officially decreed time – the UK government’s initial instructions to those with Covid-19 symptoms to isolate for a mere 7 days – and the time of lived experience – waking up with a weight on my chest for approximately the 47th morning in a row? It was grimly appropriate that a sympathiser of Slow Food and Slow Academia should end up catching (probably – impossible to be sure in the absence of testing) what we might call Slow Coronavirus. Doctors told me they are seeing this ‘long-drawn-out’ version of Covid-19 in many people, though likely exacerbated in my case by the mildly immunosuppressive effects of my regular medication for Crohn’s Disease.

So perhaps I could report that I have conducted total immersion research into the history of sleep? The reversion of my sleep patterns to a pre-Industrial Revolution pattern, of ‘first sleep’ early in the evening, some hours awake, then a ‘second sleep’ commencing towards dawn, has only recently begun to progress closer to modernity.

Or perhaps I could claim to have discovered the punchline to some absurdist joke: ‘By what transport mode did the transport historian get to hospital during the global pandemic?’. As regular readers may recall from my Jolie balade à vélo in Calais [https://frenchhistorysociety.co.uk/blog/?p=1118], the fact that I cannot actually ride a bicycle has not kept bikes from playing crucial roles at unpredictable moments. So when NHS111 told me to go straight to A&E within the hour, what was I to do while not owning a car, and not wanting to infect a taxi driver? As ever, my wife had an ingenious solution – I could get on her bike while she pushed me to hospital. This proved such a satisfactory arrangement that, the second time I was sent to A&E, I eschewed the GP’s kind offer of a conventional ambulance (others, surely, needed it more than me) for the ‘bicycle ambulance’.

Or what if I claimed new insight into the limits of tendentious comparison between global pandemic and world war? Wasn’t the notion that now the enemy was here, it was too late to suppress its advance throughout the national territory, so we should make the best of a bad job by ‘taking it on the chin’ and allowing it to proceed, while building a ‘shield’ for the nation’s most vulnerable, rather more Pétain than Churchill?

Or how about claiming to have made a breakthrough by analogy with my research into the relationship between immigration policy and protest in 1980s France? The central problematic of this is to work out whether or not the Marche pour l’Egalité et Contre le Racisme of 1983 caused the Mitterrand government’s introduction of a ten year residency permit for most foreign nationals in 1984. Did public pressure influence the government, or was it vice versa, or both? What struck me as telling about the British government’s response to Covid-19 was that it presented itself as forcing a lockdown onto a reluctant public, whereas the evidence suggested it was the other way round. One long-running feature of the government daily press conference’s now familiarly repetitive format – reminiscent of teaching the same module year after year with minor variations, or performing in the same play night after night – is the first slide, showing daily levels of transport use at a fraction of their usual level. While the spin put on it has been to compliment the British public on their obedience to the rules of lockdown, the left hand part of the graph inadvertently reveals (a case of what Arthur Marwick used to call ‘Unwitting Testimony’) that demand for transport was already collapsing before the lockdown. I suspect that future historians will find that one of the multiple causes of the lockdown was that citizens had already begun a kind of ‘lockdown from below’.

But in reality I can claim none of these things. The best I can say about my extended self-isolation is that – privileged by the gender dynamics of being banned from the kitchen for obvious hygiene reasons – I passed the time with a festival of reading unread books, watching unwatched DVDs, and listening to hitherto undiscovered podcasts. Largely freed from daily chores, were it not for being ill it would almost have felt like my biannual research trip to Paris. So in some ways I’ve enjoyed lockdown, though I feel guilty for thinking it while so many are suffering. For grubby selfish reasons, as well as the obvious public health ones, I am apprehensive about the prospect of lockdown ending.

I like to think that I’ve never bought into the cult of activity for activity’s sake that characterises much of modernity in the English-speaking world. Part of the appeal of France to me was what seemed its refreshing cultural resistance to productivism. But I don’t always practise what I preach. In ‘normal’ times the long days of teaching and commuting when I leave home at 6.45 am and return at 9.30 pm make me as much a collaborator in the cult of late-capitalist busyness as the next citizen of UK plc, where those of us living with chronic illness have become world-leading experts in the arts of ‘passing as well’. So for the first couple of weeks or so I mistakenly tried to carry on working from home. I have to think of my students, I told myself, to check they are OK, and salvage the remainder of their modules online before the Easter break – even as the spasms grew while I typed. Only after that did I give myself permission to phone the GP, see sense and rest. The thing about a global pandemic, as opposed to your common-or-garden ‘underlying health condition’, is that everyone understands, because everyone is at least vicariously experiencing it at the same time. In the unusual current climate, it is socially acceptable to be ill.

So, here are some random France-related snippets from my pause on ‘real life’:

- Thought: is there no sphere of endeavour, however dire, that does not sooner or later get turned into an Anglo-French competition?

- French politicians have of course not been spared from the deadly impact of Covid-19. There is a curious symmetry between the life trajectories of two of the best known fatalities so far from this group: both of the 1968 generation, one had moved from ultra-right to centre-right, and one from ultra-left to centre-left. Patrick Devedjian (1944-2020) was a streetfighting neo-fascist as an Occident activist in the mid-60s, but forty years later a respectable ministerial stalwart of the UMP; while Henri Weber (1945-2020) commanded the Ligue Communiste’s service d’ordre in its Molotov cocktail-wielding apogee of the early 70s, before the man who had once theorised the collapse of social democracy ended up a PS Senator, as close an associate of Laurent Fabius as Devedjian was of Nicolas Sarkozy.

- The first thing I could face reading, as an escape from wall-to-wall Coronavirus on all channels, was Sainte Anne! by Airy Routier and Nadia Le Brun. Given my ongoing research into the politicisation of transport policy in modern Paris, I had been meaning for a while to read what turned out to be a rather thin hatchet job on Anne Hidalgo, for the sake of balance to Respirer, Hidalgo’s defence of her sustainable transport policy. Just in case Hidalgo was voted out, I had set myself the deadline of March’s local elections to read Sainte Anne!, only to find the second ballot postponed even as I neared the end of the book, so I needn’t have rushed.

- Résistances by Jean Salem, Sorbonne philosopher and son of the famous Algerian Communist militants Henri and Gilberte Alleg. A readable extended autobiographical interview – interesting on his unusual upbringing between Algiers, Moscow and Provence. While Salem’s opinions remain the predictable ones of a Communist diehard, he makes a spirited case against celebrity ‘star systems’ in intellectual life and the subordination of universities to utilitarianism, and for the role of high culture in ‘levelling up’ society.

- The Reader On The 6.27, a novel about a commuter by Jean-Paul Didierlaurent. Diverting, but the plotline is a little too disturbing to fully work as the feelgood read the back cover promised – so not ideally recommended for reading while masked up in the A and E ‘red zone’ awaiting the results of your chest x-ray.

- Parisian Lives: Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir and Me by Deirdre Bair. As fascinating as you might expect given the two subjects of Bair’s biographies. But also most illuminating on the petty jealousies of scholarly life and the shocking levels of overt sexism in 1970s American academia. Highly recommended for PhD students and early career researchers wanting to discover how research on living subjects is really done in practice.

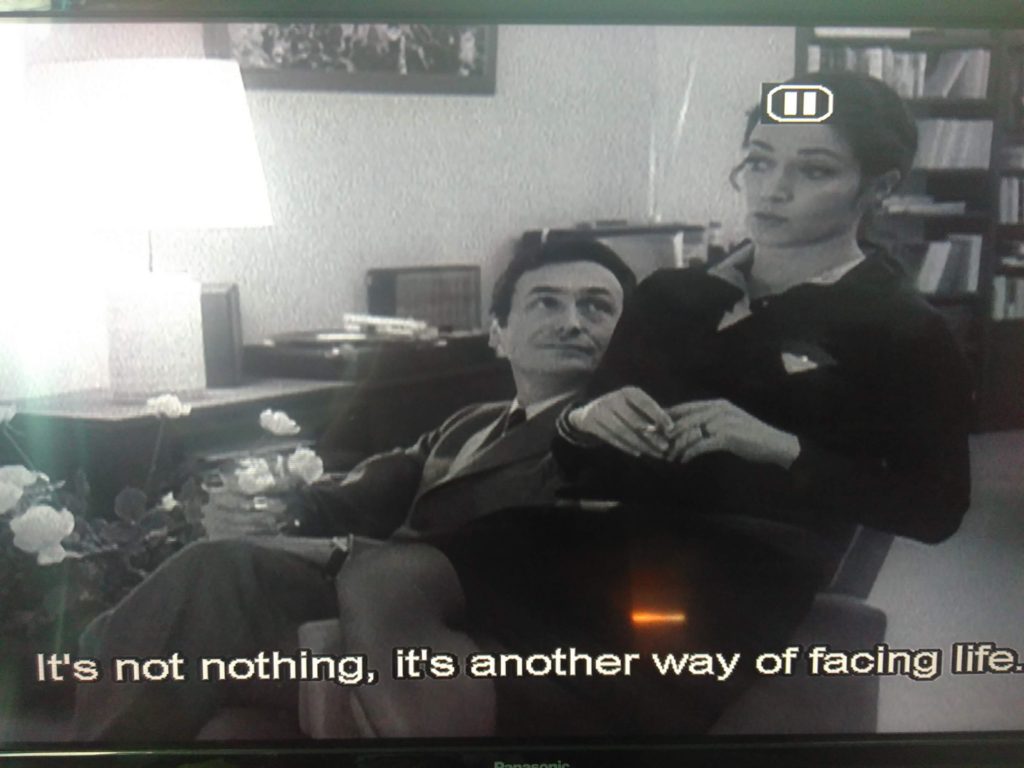

- I curated my own personal mini-festival of French New Wave cinema: one film each by three of the best-known nouvelle vague directors. (A colleague jokes that I could get thousands of hits online by narrating my mini-festival as a ‘watching party’ in the style of Tim Burgess’ lockdown ‘listening party’. Though I only really ‘curated’ it in the sense that these were some of the DVDs I happened to have at the back of the cupboard in my isolation zone – which is like saying I ‘curated’ the just-add-boiling-water instant sachet of Borscht soup also found at the back of a cupboard, which I drank while watching the films). The portentous profundities of Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010) were a bit much to absorb in the circumstances, so I switched to lighter romantic comedy with Truffaut’s amusing L’Amour en Fuite (1979), depicting the further adventures of the now (not very) grown-up Antoine Doinel from Les 400 Coups in a Giscardian world of newly liberalised divorce laws. But my favourite of the trio was Rohmer’s wonderfully atmospheric Ma Nuit Chez Maud, starring Françoise Fabian and Jean-Louis Trintignant – surely a contender for the title of ‘second best film made in Clermont-Ferrand in 1969’, after Le Chagrin et La Pitié. Ma Nuit Chez Maud captures classic French philosophical themes like Christian-Marxist dialogue and the clerical/anticlerical divide, through the simple prism of a classic love triangle unfolding over 24 hours. Will the uptight Catholic bachelor and the vivacious divorcée from one of the oldest Radical families in Clermont, to whom he has been introduced by his old mate, an academic philosopher and card-carrying PCF member, spend the night together or not? And what would Blaise Pascal have said about it?

- Just for fun, I re-read two of my favourite bande dessinées. Quel homme choisir? De gauche ou de droite? by Du Peloux, Schmuel and Antilogus is a hilarious romp through stereotypical modern voter demographics. It nails the foibles of rightwing and leftwing men alike: l’homme de droite sits in his armchair with a newspaper as his wife hoovers around him, whereas l’homme de gauche does exactly the same – except thinking he is helping by reading items from the newspaper out loud to her. Meanwhile Platon La Gaffe: survivre au travail avec les philosophes by Jul and Charles Pépin imagines a work experience placement in a large dysfunctional modern workplace staffed entirely by eminent philosophers. Walter Benjamin directs the photocopying department, Friedrich Nietzsche is HR Director, and the union reps are Karl Marx and Thomas Aquinas, while Michel Foucault (who was actually once Henri Weber’s line manager, in so far as such a concept existed at the philosophy department of the Centre universitaire expérimental de Vincennes in 1969) operates the CCTV cameras.

Now, as I tentatively venture outside, to walk for the first time in a changed world, what is going on? In a superficial sense – for substantial if limited sections of the population, very unequally distributed by class, ethnicity and gender – the present moment is every wildest deep-green / anarchist / eco-socialist / anti-capitalist / post-work fantasy come true all at once. You could call it ‘a holiday at home’. You could call it an extended grandes vacances. You could call it ‘a sabbatical’ (usually more fantasised about than witnessed in the post-92 university sector). We are all utopian socialists now.

So, my inner André Gorz, José Bové or Paul Ariès has been longing to excitedly exclaim, with some exaggeration: ‘Even Anglo-Saxons are being paid by their government not to work! More time for more people to lie in hammocks reading books! A nation of shopkeepers have discovered the importance of mutual solidarité! Meanwhile ducks are striding the deserted streets of Paris like they own the place! What’s not to like? Let’s extend this lockdown until that curve reaches zero, no-one has Coronavirus anywhere, and into the bargain, the climate crisis has been solved! Keep big businesses shut – but open up the park benches, symbol of the joys of economic inactivity! We can all keep this up for, say, 12 years – until I’m 57, the earliest I can cash in my teacher’s pension! Then I can bid farewell to this métro-boulot-dodowage-labour racket for good, without ever commuting to work again! At last my real, non-alienated work can begin!’.

I can, though, hear Toni Negri off stage left, flanked by a menacing posse of face-mask-clad heavies from 1970s Italian operaismo, shouting ‘You, the employee with some degree of job security! Think you can just work from home forever? Still collecting your salary while we fester in oppression? You privileged bastard! The precariat’s coming to get you!’. As Covid-19 interacts with global inequalities, the utopian visions start to break down. So to welcome the current crisis is the eco-socialism of fools. Serious advocates of degrowth have been at pains to point out that despite the real opportunities for rethinking society that it is permitting, a plague of death and destruction plus slump really does not represent a viable model for the coming necessary transition away from the carbon era. In other words: ‘It’s décroissance, Jim -but not as we know it!’.

That said, it’s a rare moment in contemporary anglophone society that not doing things has acquired an aura not of self-indulgent indolence but its own distinctive moral halo. By far the most important thing I have done in the current crisis was to not hold the exciting day conference I had planned for my undergraduate students on ‘1989-1990: Birth of Contemporary Europe?’, but which could have become, it is awful to think, a virus breeding ground. While I had a slight 24 hour fever in mid-February (well before I began to take Covid-19 seriously, let alone consider the possibility that I had it myself), the first symptom I did clearly identify – the now notorious dry cough – arrived on 13 March, immediately after the UK government ordered anyone with one to self-isolate. And luckily therefore just in time to give me a good reason, during the dwindling days of UK academia’s ‘business as usual’, to cancel the 16 March conference. I have been not organising conferences for a couple of decades now, but the one time I did spend months organising one, only for it not to happen, was the most significant of these non-events. Of course I was far from alone in doing my bit by merely not doing things. My inbox in mid-March rapidly filled with announcement after announcement of events not taking place. Very soon, the authorities would be forced to follow suit. It was now not just permissible to not do things, it was ethically right and legally compulsory to not do things. Future historians may debate whether or not, in the spring of 2020, the cult of activity which had been the predominant religion of the preceding couple of centuries of western civilisation, suddenly reached a full stop. Or was it just replaced by its offshoot: the cult of ostentatiously doing things, but doing them virtually?