Paper Title: Empire of Taste: French Commodities and Global Power in the Nineteenth Century

Speaker: David Todd (KCL)

Chair: Dr Simon Jackson (Birmingham)

Date: 17 October 2018

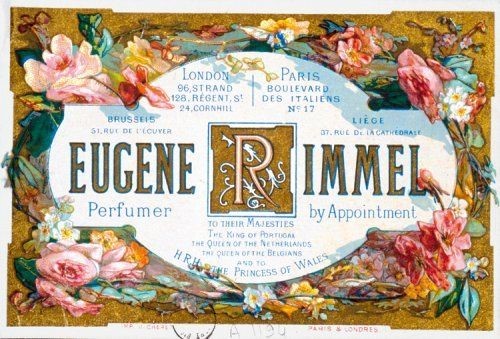

Eugene Rimmel’s business card, by Jules Chéret, from the Driehaus Museum

For this week’s seminar, Modern French History teamed up with Rethinking Modern Europe to enjoy some of the finer things in life. Champagne, velvet, prêt-à-porter dresses and high-end mascara: all were there to be savoured on a warm Wednesday evening… but alas only in PowerPoint slides and David Todd’s mellifluous prose.

It is fair to say that France has a global reputation for luxury commodities. When we try to imagine the origins of this stereotype, we probably conjure up images of the court culture of the Sun King, or the indulgences of Marie-Antoinette. But Todd implied that we might spend less time among the courtly graces of the ancien régime, and more exploring that long stretch of the nineteenth century when France was ruled by kings and emperors – i.e. almost all of it.

While this period so often seems to feature only as a deviation from the ‘exceptional’ path of French politics and society that takes us from the First Republic to the Third, it witnessed the emergence of a ‘neo-courtly’ bourgeoisie and, in Todd’s argument, a dynamic, specialised, export-oriented consumer economy. Far from languishing, French export volumes between 1850 and 1870 rocketed from around half of the British to nearly drawing level. Innovation was aided by immigrant entrepreneurs like Rimmel, Bollinger or Krug, who cultivated products to export markets that they knew well. By the mid-1860s, France was only the fifth largest consumer of its most famous sparkling wine.

Todd also wants to show that this is a story that cannot be told without empires. If French industries fed a burgeoning global demand for goods like articles de Paris that became intrinsically associated with the brand of France in western markets, this economic success in this period hinged on the propensity to collaborate with other empires. The French economy became highly dependent on raw materials from the British colonies. Dependency on British imperial supply chains fuelled French backing for the British in China, Syria and Suez.

At the same time, Todd wants to suggest that the French economic model encouraged a peculiar model of colonial expansion, where countries like Mexico and Egypt were subject to ‘informal’ French hegemony (and also through what we might call ‘soft power’ in other markets). This ‘velvet empire’, as Todd calls it, helped secure France’s global position during the middle of the century. Its dramatic collapse during the economic crisis of the 1870s might have something to do with France’s equally dramatic expansion in direct colonialism at the end of the century.

Rob Priest (RHUL)