by Alexandra Stuart & Sophie Rees.

The first panel of A Date with History produced an illuminating insight into the concept of haute couture as integral to French culture, whilst questioning its perception and identity as exclusively French, given its widespread exportation and appropriation abroad.

In the wake of her current exhibition at the V&A, ‘Christian Dior, Designer of Dreams’, curator ORIOLLE CULLEN cast Dior as the ultimate case study for Parisian fashion in the last seventy years. Cullen first conveyed the mixed response both home and abroad to Dior’s 1947 debut. The international fashion press raved about his ‘New Look’, which with its sloping shoulder line, tiny waist, padded hips and calf-length skirts was a stylistic rebirth after the boxy war-time silhouettes. But the couturier’s flagrant display of luxury also attracted criticism in the societal context of post-war hardship and rationing. Cullen quoted British historian James Laver, who had complained that Dior’s skirts would never catch on, as they drew attention to the ankles and feet, “neither of which were a British woman’s strong point”. Despite initial criticism, Dior succeeded in building up an international fashion empire, opening branches in countries from Venezuela to Japan. While Dior continued to draw inspiration from the femme Parisienne, ‘crystallizing the look of fashion’ for decades, he opened haute couture up to a wide and diverse audience. Finally, Cullen returned to the question at hand, highlighting how designers from all over Europe, such as Gianfranco Ferré (Italy) and John Galliano (Britain) have taken up creative directorship at Dior and produced ingenious haute couture that is anything but purely French.

In the wake of her current exhibition at the V&A, ‘Christian Dior, Designer of Dreams’, curator ORIOLLE CULLEN cast Dior as the ultimate case study for Parisian fashion in the last seventy years. Cullen first conveyed the mixed response both home and abroad to Dior’s 1947 debut. The international fashion press raved about his ‘New Look’, which with its sloping shoulder line, tiny waist, padded hips and calf-length skirts was a stylistic rebirth after the boxy war-time silhouettes. But the couturier’s flagrant display of luxury also attracted criticism in the societal context of post-war hardship and rationing. Cullen quoted British historian James Laver, who had complained that Dior’s skirts would never catch on, as they drew attention to the ankles and feet, “neither of which were a British woman’s strong point”. Despite initial criticism, Dior succeeded in building up an international fashion empire, opening branches in countries from Venezuela to Japan. While Dior continued to draw inspiration from the femme Parisienne, ‘crystallizing the look of fashion’ for decades, he opened haute couture up to a wide and diverse audience. Finally, Cullen returned to the question at hand, highlighting how designers from all over Europe, such as Gianfranco Ferré (Italy) and John Galliano (Britain) have taken up creative directorship at Dior and produced ingenious haute couture that is anything but purely French.

It seemed fitting for SOPHIE KURKDJIAN (CNRS/IHTP historian) to then invite the audience to deconstruct the clichés of the ‘fashion capital’ and the ‘Frenchness’ of haute couture, which the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, the regulator of the couture system, helped establish. It came as a surprise to some that the origins of the haute couture system lie with a Briton, Charles Frederick Worth, who founded the House of Worth in Paris in 1858, a fact emblematic of the multiculturalism amongst Paris’s most renowned designers. Kurkdjian went on to emphasize the impact of migration in the last century on the development of industry techniques and styles. The atelier became a refuge for many skilled textile workers who had fled their homes in Eastern Europe due to genocide and war; their contribution cannot be easily quantified, but it ought to be recognised and valued. Kurkdjian’s research encourages us to question the myth of strictly ‘Parisian’ fashion and see haute couture for what it truly is: a transnational construction.

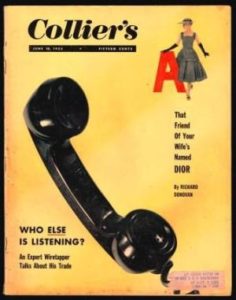

FARID CHENOUNE (Institut Français de la Mode) focus was sociological, considering the husband’s perspective of couture and the sexual status of the couturier. Chenoune first examined the cover of a 1955 issue of Collier magazine entitled ‘That Friend of Your Wife’s named Dior’, revealing the American man’s irrational and ironic anxiety towards the platonic ‘Third Man’ in his relationship who dresses his wife. Chenoune began a close character analysis of Christian Dior, the ‘ceremonial’ relationship he had with his clients, in which Dior played the role of chevalier servant (the knight in shining armour). In la cabine, the sacred fitting room of the couture house, Dior upheld an ‘unspoken contract’ with his client’s husband whereupon he did not touch or desire her, rather appreciated her as an ‘artefact’, a vision of hyperfemininity. For Chenoune, this concept is comparable to the scenes in Montmartre’s cabarets, where dancers would dress to please their male audience, but from a spatial and physical distance. Finally, Chenoune questioned whether French nationhood, entwined as it is with the notion of haute couture, should also be perceived as ‘weird, magical and fantastical’ due to its cabaret origins.

Keen to shatter stereotypes through applied theory, CAROLINE EVANS (University of the Arts London) questioned the title of the conference, viewing fashion as a transnational hybrid rather than an autonomous, national product. Nevertheless, by offering a historical reappraisal of Franco-British relations, Professor Evans illustrated the root of extant stereotypes, in which the sartorial was viewed through a satirical lens. From as early as the sixteenth century, an emphasis on classification has inhibited the diversification of fashion. Furthermore, a rhetoric of ‘us’ and ‘them’ emerged that has continued to plague the fashion industry, manifesting itself today as cultural appropriation. Evans contends that although caricaturists like Darley and Bunbury may appear harmless, their drawings reveal crude generalisations that are rooted in a warped sense of ethnocentrism. However, Evans idealistically outlines the arrival of globalisation as heralding a new era. Here, national identity is not fixed, but contingent, and stereotypes are worn as badges of honour, reflecting the porosity of borders and ideas.

To conclude, JENNY LISTER (V&A curator) delivered an incisive commentary on the museum’s current retrospective on Mary Quant. Drawing upon her comprehensive knowledge of this Sixties icon, Lister paints an intoxicating picture of Quant as the face of Swinging London. From her small boutique on King’s Road, Quant had an immeasurable impact on the democratisation of fashion, by creating affordable designs for the youth market. Significantly, Lister dispels Quant’s invention of the miniskirt as a myth, claiming this thigh-high sensation was an international improvisation. Nevertheless, Lister contends that Quant used British stereotypes to her advantage, by subverting traditional motifs yet working within the infrastructure of the cottage industry and later, on a global industrial level. By satirising stereotypes, Lister argues that Quant not only blurred the boundaries of credibility, but also those of gender and identity. The distinction between mens and womenswear had become harder to pinpoint, with androgynous styles favoured internationally by the 1970s. Consequently, Quant’s inversion of tradition and expectation created a brand that catered to international tastes but remained distinctly British in flavour.

The panel discussion, chaired by SHAHIDHA BARI (London College of Fashion), followed in a similar vein by focussing on the permeation of fashion across borders and time periods. Cullen emphasised the timeless appeal of Dior’s ‘New Look’, with many elements of the iconic silhouette being incorporated into contemporary collections. Similarly, Evans illustrated the diffusion of fashion across accepted boundaries, through the ‘masculinisation of the female wardrobe’. This was tempered by Chenoune, who advocated that women have two wardrobes, as opposed to the sole male wardrobe, a point with which Evans agreed. Although this astute observation rescues female fashion from patriarchal infringement, the tendency to pigeonhole gender into binaries still plagues fashion theory. The location of the new fashion frontier was a question that greatly excited the panel. Both Kurkdijan and Cullen praised the emergence of the African fashion scene, which the former argued was authentically relayed to the international market. Nevertheless, Chenoune’s concerns over cultural appropriation are well-founded. Despite the industry’s best efforts, the vogue for national stereotypes continues.