Date & Place: Monday 8 January, at the Institut Français, South Kensington

Speakers: Professor Malcolm Crook (Keele)

Paper Title: How the British and French Learned to Vote

Chair: Professor David Andress (Portsmouth)

To listen to a recording of the event, click here (right click to save as MP3)

On January 8th, 2018, at the Institut Français, the SSFH and ASMCF held their 8th annual Douglas Johnson Memorial Lecture. It was a successful sold out event, which was preceded a committee meeting and the public presentation of our Undergraduate Dissertation Prize. After an introduction from the Director of the Institut Français, Claudine Ripert-Landler, and the Society’s President, Professor David Andress, our invited speaker Professor Malcolm Crook gave a lecture entitled ‘How the British and French learned to vote’. This was a sweeping and insightful study that considered the practicalities of voting and their wider political and cultural significance, rather than simply focussing on who was being voted for. That, he said was a lucky fact, relating his own electoral misadventures in the 1970s, where after a fascination with the process of voting had supplanted his own ambitions for electoral office. The symbolic image of the ballot box was at the centre of the act of voting, and indeed, at the centre of the lecture. At issue was how that ballot box was interacted with: by single voters or plural votes, by men and women, and in secret or in the open. The ways in which these questions evolved was an important aspect of the evolving political cultures of both France and Britain, and showed moments of interaction and opposition.

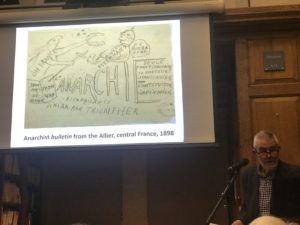

Professor Crook examined a series of spoiled French ballot papers, which were retained by electoral commissioners centrally to check that the votes had been legitimately disqualified. These ballot papers generally related to legislative elections, and were held at the Archives Nationales, with local ones being held in various Departmental archives. From this analysis came a wonderful array of illustrations, annotations, and even essays on why individual voters felt unable to cast a simple ballot. From explanations why certain candidates “rogues” or “dirty dogs”, to write ins for public intellectuals, these were not merely a dereliction of electoral duty, but rather a form of civic abstention. Professor Crook showed ballots from the period of the Dreyfus Affair, with sketches valorising and demonising both sides. This zeal for or against specific candidates was part of a wider “esprit frondeur”, which took an active joy in desecrating the “quasi-religious” act of voting.

Indeed, the sanctity of that vote was important. The audience heard about mock elections held in 19th century French schools, which were designed to draw children from the confessional to the ballot box. We also heard about the varied adoption of curtained “isolatoires” or voting booths (introduced in 191), which allowed true independence in front of the electoral urn, a fact which some conservative opponents worried would be disruptive. Professor Crook reeled off a litany of critiques: that the booths were too like the confessional, might be confused with a toilet, or might even offer a convenient snug for amorous voters caught up in electoral passion.

Turnout too was something which evolved over time in France and Britain. In both countries, turnout grew dramatically at the end of the 19th century, a level which it largely maintained until a drop-off in the last three decades. Professor Crook drew allusions to a sense of decline in civic society rather than any death of ideology as a pattern of intermittent voting took over from the 1980s. Voting as a social ritual suffered when other social rituals fell away, remaining more resilient in smaller communities even as it faltered amidst urban anonymity. That idea of anonymity was an important theme of the lecture, and the power it implied for individuals was palpable. One 1898 ballot paper boasted about being “souverain anonyme d’un jour” (anonymous king for a day), expressing firmly held and strongly felt beliefs on a much broader system. With accounts of counts, and the tension of abstention, the act of voting became woven into the fabric of French and British lives, but it did not do so of its own accord. Ultimately, this question of sovereignty, of citizens and subjects, was the distinction drawn between French and British voters. Both sets of electors had to learn to vote, even if that was often marked by a wider and messier public discussion than a printed name or clean cross on a ballot paper.