In the latest in our series of ‘Hors d’oeuvre’ posts on the new Special Issue of French History on material culture, we caught up with Prof. David Hopkin to talk about his article on lacemakers’ tools.

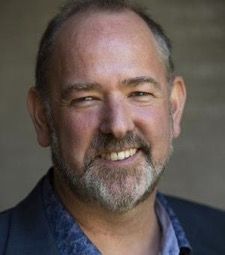

David is professor of European social history at the University of Oxford. He arrived there via the Economic and Social History Department at Glasgow, but started his research at Cambridge under the supervision of historical anthropologists – Peter Burke and Bob Scribner. He is also the current President of the Folklore Society.

Hi David, thanks for joining us to talk about your new article. What do you think will most surprise readers in what you have to say?

The evidence of lacemakers’ corporate identity, their pride in craft, should surprise labour historians given how often it’s been accepted that this was not a feature of female dominated trades. I don’t think it will surprise readers that lacemakers’ anthropomorphised their tools, that they became forms of self-expression and means to embody relationships, because we all do that to an extent, just as we all have mixed feelings about work. What might surprise is how strong, and polarized, these symbolic resonances were in the case of lacemakers.

Do you have a favourite example or anecdote you came across in this work?

This example comes not from France but from the English Midlands, and specifically a story told by John Plummer, a ‘worker-poet’, in an 1878 article on the lace industry for the Northampton Mercury:

… a lacemaker died and after the funeral a claim was made for certain moneys alleged to be owing. The daughter was convinced that the claim had been satisfied, but the receipt was nowhere to be found. An execution was put in, when a struggle took place for the ‘pillow,’ which the daughter was determined to retain as a memento of her deceased parent. During the fray the outer covering became torn, and out fell a folded piece of paper, which proved to be the missing receipt.

The novelist Ignazio Silone says somewhere that the anecdote is working-class philosophy: there is quite a lot conveyed in this short narrative: the lace-pillow as an intimate object where lacemakers’ kept secrets, as a physical embodiment of lacemakers’ relationships… But the folklorist in me can’t help pointing out that there’s a folktale lurking behind this anecdote (ATU756C* to be precise). And that says something about the relationship of culture, in this case lacemakers’ oral culture, to experience, because such things did happen.

What’s the thing you most regret having to leave out of this piece?

I’m sceptical about the significance of national units for social history. Lacemakers in different countries sang the same, or at least analogous songs, practiced the same rituals… But given that this chapter grew out of a seminar series on ‘Material France’ and is appearing in French History, I had to keep the focus on the hexagon.

Yet if aspects of lacemakers’ culture were transnational, their language was regional. I couldn’t convey the richness of these dialects. I rely a lot on the oral history interviews carried out by Dominique Sallanon in the Velay. She and her interviewees mostly spoke French, but now and again they broke into Occitan. For instance, when Dominique got out examples of patterns, one lacemaker exclaimed ‘Notra Pointa!’ This was ‘our thing’ expressed in ‘our’ language.

Can we talk about the backstory to the article? How did you first get interested in this topic?

Songs were the starting point. Lacemakers sang while they worked, and these songs can tell us about their lives. In the 1860s a local judge, Victor Smith, collected lacemakers’ songs in the Velay and I went to Le Puy to research the singers in 2004. While there, in a newsagent’s I picked up two autobiographies of lacemakers, edited from interviews conducted in the 1990s. So I began to understand the context of these women’s working lives.

This article grew out of a project with an anthropologist, Nicolette Makovicky, who studies contemporary craft communities in the former Soviet bloc. I’ve drawn a lot on her work, as well as discussions, nearly two decades ago now, with Bruno Ythier and Dominique Sallanon at the lace museum in Retournac. But they didn’t read drafts!

Are you a ‘plan it all in detail’ writer, or a ‘start writing and see where it goes’ person?

Definitely the latter. It’s a problem so I regularly try to be more methodical. But it never comes off, because it’s only in writing that I find out what I want to say.

Do you have a cure for writer’s block? We ask everyone this question because we live in hope.

I write quite a lot, perhaps too much, but my focus is always on the miniature. I doubt I’m ever going to author the BIG history of the French Revolution. But I hope there is also room for the small-scale, the intimate, the mundane.

Whose writing do you most admire and why?

I enjoy reading what the French call ‘ethnologie’. I’m currently trying to write something about Daniel Fabre, professor of European Anthropology at the EHESS, who died in 2017. ‘Ethnologie’ is usually very local, tied to the particular, but Daniel had huge breadth of vision, both temporal and geographical. His ability to draw insights from disparate sources can be breath-taking.

But as Daniel would be the first to admit, the greatest anthropologists are novelists, and the one whom I’m reading most at the moment is Marguerite Yourcenar. Her family came from Bailleul, a lacemaking town. She is wonderfully clear-eyed about her own genealogy, weaving the stories of her ancestors into larger historical narratives.

What do you think helpful feedback on writing involves?

My mum used to read my work – she’s unsentimental about ‘strangling one’s babies’ for the sake of clarity, such as deleting all the alliterations to which I am addicted.

What’s the word you can never type right?

Phenomenon. Can’t say it, can’t write it.

What are you working on next?

More on lacemakers. And if I ever finish with them, then something on the memory of seigneurialism, as conveyed in folk narratives about shepherdess saints and eternal hunters.

If you could see one change in academia in the next five years, what would it be?

It may be an age thing, but I’m quite gloomy about the future of the humanities, and my hope for the next five years is survival. I worry about everything – the decline of languages in UK schools, the lack of funding for graduates, especially masters… because that’s the moment students have to make a decision. No funding, no real career path, increasingly poor pay… all these will mean that academia might become, as my father termed it, ‘out-door relief for the propertied classes’. But if I could bring about change, I’d like masters courses to focus more on new methods, new technologies. We have so many tools now but we, including me, don’t know how to use them.

Éclair or saucisson?

My doctor has, in unequivocal terms, told me the answer is ‘neither’.