Roxanne Panchasi is an Associate Professor of History at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada who specializes in twentieth and twenty-first century France and empire. She is the author of Future Tense: The Culture of Anticipation in France Between the Wars (Cornell University Press, 2009). Her current research focuses on the cultural politics of French nuclear weapons and testing since 1945. Her most recent article, “‘No Hiroshima in Africa’: The Algerian War and the Question of French Nuclear Tests in the Sahara” appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of History of the Present.

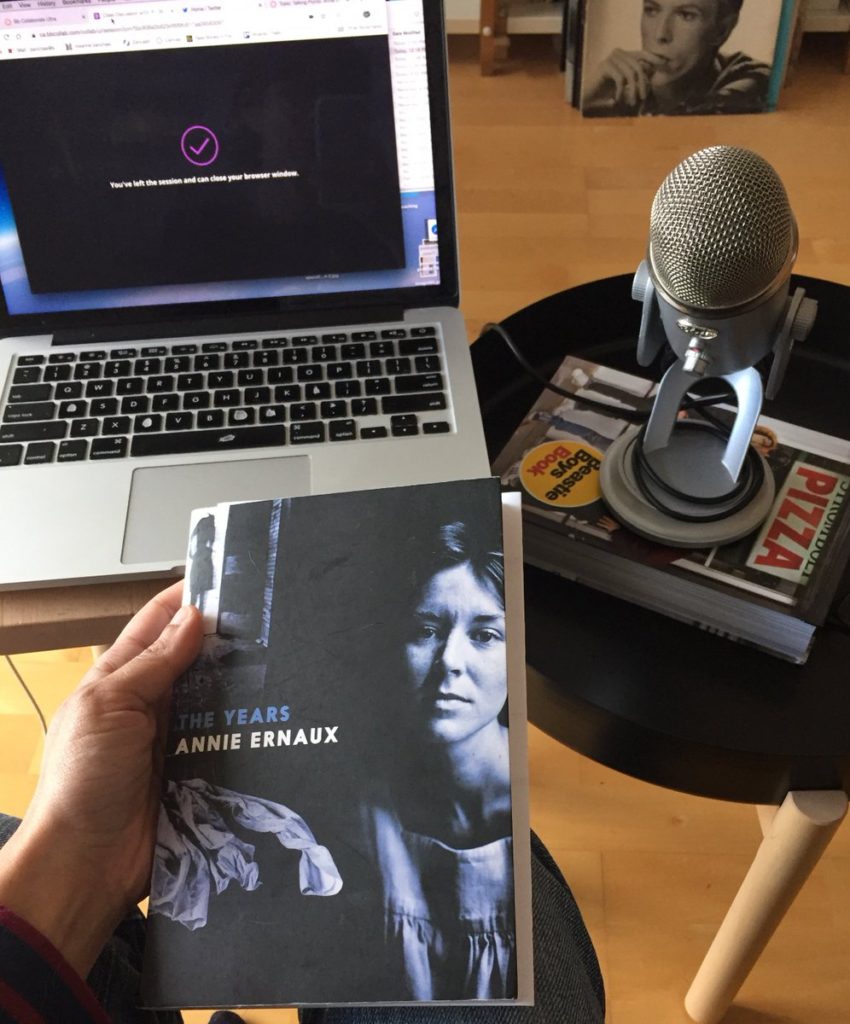

March 10, 2020: Last day of face-to-face teaching. My modern French history class had just finished discussing the Second World War and my students were reading Annie Ernaux’s Les Années (The Years). Our final on-campus exchange happened in tutorial sections after lecture. We talked about history, memory, and autofiction. I asked each student to create two timelines spanning from the year of their birth to 2020. On one, they plotted 10 personal milestones. On the other, 10 events they think of as historically significant in a broad sense. Then we had a conversation about any relationships they noticed between the two timelines. A few students remarked that their lives seemed relatively disconnected from major historical events, that they felt insignificant by comparison. It seemed as if nothing much had happened to them yet.

The next day, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. On March 12th, the health authority in British Columbia strongly recommended the cancellation of all non-essential travel, and gatherings of 250 people or more. My university decided to move all instruction online within the next week. I never saw my students again in person. I’d be willing to bet that every one of them has felt a correspondence between their personal experience and world history since.

March 13-May 4: Frenzied “pivot” to teaching online. I was lucky that most of my course materials were available electronically. But what did I know about recording lectures or teaching remotely? ZERO. I made many mistakes in these weeks as I tried to get us all through with as little stress and as much compassion as possible. My students were dealing with a lot and I was darting in 70 different directions in a two-bedroom apartment: solo parenting and homeschooling a kid while “at work”; trying to figure out new platforms and apps; running class sessions online; coming up with asynchronous alternatives; grading; panicking about every person and surface I came into contact with; sewing face masks obsessively. I think it was all as okay as it could have been in the end. It’s a bit of a blur now. Somewhere in there, my institution decided teaching would continue at a distance through the summer. Struggling to get one term wrapped up, I had a few weeks to redesign a six-week, writing-intensive seminar on France and the Second World War (HIST 417) scheduled to begin in mid-May.

Reimagining my course in the anxious and confusing space-time of “the new normal” was tricky. All my pedagogic comforts and strengths seemed to lie in things that had become virtually (HA!) impossible: spontaneity, connection, picking up on cues from the way students react and interact, with me, the material, each other. Being recorded on video makes me uncomfortable. Lecturing is definitely not my teaching superpower. Trying to lecture while staring at a computer screen, or worse, an image of myself staring at myself on a computer screen, feels impossible. I figured I was done for.

Then a friend (I’m looking at you, Alexander Dawson) reminded me to be myself, to lean into what I already know how to do, to stop trying to become a new teacher and focus on staying the one I already am as much as possible. And it occurred to me that I’d spent the last several years developing some skills when it came to one form of remote intellectual exchange: podcasting. My six plus years of experience with New Books in French Studies had taught me things I could use now. Time and again, interviewing people about their work had shown me that it’s possible to have an engaging, productive, sometimes funny, even intimate, scholarly conversation at a distance, even with people you’ve never met before. It has also helped me build an outstanding network, including former interviewees and listeners, people I could turn to for suggestions and advice. This is how RADIO 417 came to be…

Finishing up one term while rethinking the next, I mapped out a series of 11 pre-recorded broadcasts, each featuring a French song/composition from the World War II era to complement the chronological and thematic units of the course. I contacted a number of colleagues. Some I’d known for years; others I’d only met through social media. I asked if they might have time to listen to a song and speak with me, about their own related research, but also about things like melody, lyrics, performance, affect, the wide and lasting impact a piece of music can have. Almost everyone I approached said yes immediately. Those who couldn’t spare the time in the chaos of the moment (totally fair) suggested others I could approach. The planning stage alone was a tremendous reminder of how vital professional generosity and solidarity can be. So much academic work happens in isolation. But we don’t always have to operate in silos, especially now.

May 5-May 11: I submitted my Spring term grades on May 4th and went into high gear remaking my Summer course on Canvas, my school’s online learning management system. Having only really used the tool as a glorified file cabinet before, I had so much to learn. I also needed to find online materials my students could access for free without violating copyright, to plan synchronous seminars and asynchronous content (discussions, written assignments, peer response exercises) students could work on in their own time. I wanted to check in with the students too, find out what their experiences with remote learning had been thus far, what worked and what didn’t; what they had access to in terms of technology; and to try to help them get the tools they’d need if they were missing any essentials. And I had to check in at various institutional levels to make sure I was following existing, new, and evolving policies. In order for RADIO 417 to work, I also needed to get a few broadcasts recorded and edited ahead of time. In the days before my course began, I was glued to my decrepit laptop. My son will most certainly remember this as a borderline neglectful period of his childhood.

May 12-June 18

Summer term started, fully remote from the outset. I’d worked with some of the 19 students enrolled in my seminar before; the rest I’d never met. As I write, we are in the final week of the course. My students are exhausted, and so am I. The whole endeavour has involved so much more labour than I could have imagined, and I note this as a faculty member who enjoys the privilege of a full-time, permanent position. The experience has been difficult, but also sort of wonderful, in no small part thanks to the series of broadcasts my colleagues and I made together.

Since the new term began, I’ve kept recording and editing at all hours of the day and night, managing technical glitches (and at least one major fail!). I’ve spoken with historians of France and empire from the 17th to the 21st century, and have also recorded the voices and ideas of scholars of literature and sound. The broadcasts explore a range of themes: the history of radio and propaganda; gender and sexuality; mourning, melancholy, nostalgia, and anticipation; music composition, genres, performance, and reception; wartime collaboration and resistance; nationalism and imperialism; military turning points, high politics, and the experiences of ordinary people, from the eve of the war to the Liberation.

While I never would have wished for the situation in which I’ve been teaching these past few months, it has pushed me to experiment in ways I might not have otherwise. Each week of the past six, my students have listened to one or two short broadcasts, sharing their responses to what they’ve heard via an online discussion page. By the end of the course, they’ve gained a meaningful sense of the soundtrack of this era in French history that has deepened their understanding of the other materials in our course: primary and secondary written and visual sources, the art, propaganda, and film of the period. Giving my students something to listen to and not look at has also meant allowing them to step away from their screens, to close and rest their strained eyes, sometimes even to walk outside and get some fresh air while being “in class”.

Offering students a flexible way of engaging with our subject, and with one another, RADIO 417 has also done so much for me. A moment of scholarly and human connection with each of my guests, the recording sessions have taught me so much, about France’s wartime history, of course, but also about the power of music and multiple voices at a time of crisis. In a way, RADIO 417 became a kind of accidental COVID archive. Speaking to me from homes in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., and France, each one of my far-flung interlocutors began our conversation by telling us where they were and how they were doing. And in these few moments, my students and I could experience a meaningful connection to a much wider world. Who knew that teaching at a distance—during such a stressful moment, and working with so many constraints—could open up this beautiful possibility while shutting so much else down? None of our timelines will ever be the same…

*****

If you’d like to listen to RADIO 417, or might find the broadcasts useful in your own teaching, please send me an email at: panchasi@sfu.ca.

I cannot begin to express my gratitude to RADIO 417’s extraordinary guests: Danna Agmon, Jonathyne Briggs, Hanna Diamond, Julian Jackson, Richard Ivan Jobs, Daniel Lee, Julie Beth Napolin, Sarah Osment, Rebecca Scales, Christopher Silver, and Andrew Smith. I’m also grateful to Emily Hooke and Nina Wardleworth for sharing their research with my class via video. Huge thanks as well to all the students in HIST 417 for working so hard and listening so thoughtfully. Finally, a shout-out to my son Gus and our dog Rudy, for the love, the hijinks, and all that waiting.