Each month, a researcher shares their experiences of using a particular archive. The overall aim of this section is to create a database of the different archives available to those working on French and Francophone studies that will be of help particularly to students just starting out in research.

Keanu Heydari is a PhD candidate in Department of History at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Here he talks about his research into material dealing with Iranian student activism and social movements in Paris.

One difficulty that presents itself when studying diasporic or exilic communities is the lack of centrally organized archival repositories. In my case, the study of Iranian student activism and social movements in Paris in the second half of the twentieth century has presented challenges to archival research as it is traditionally conceived. Rather than working through fonds of material at a couple of distinct locations, my research – at least in part – required tracing the publication history of pamphlet literature produced by the French section of the Confederation of Iranian Students, National Union (CISNU), known as the Union des étudiants iraniens en France (UEIF).

Beginning with the Archives Nationales in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine and the Bibliothèque nationale de France (François-Mitterrand) in the 13th arrondissement, I later trekked to La contemporaine in Nanterre and the Centre des Archives diplomatiques du ministère des Affaires étrangères in La Courneuve. In addition, I consulted the Universitätsbibliothek in Tübingen and the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. I write with some hesitation that my exploration of all the relevant archives Paris has to offer is not yet exhausted. Out of all the archives I have consulted, however, the Nanterre site of La contemporaine remains the most remarkable.

Architecturally stunning, Nanterre’s La contemporaine is a museum, archive, and research library that specializes in twentieth-century history. One of two campuses, the Nanterre site primarily hosts the archive while the principal museum is in the 7th arrondissement. Their website includes a timeline of the organization’s history. Built with thin layered bricks and resting on a glass-paneled mezzanine, the building certainly captures the essence of the twentieth century’s gravity. As I write from the 14th arrondissement, the trip to the archive required taking the RER B to Châtelet-Les Halles and then the RER A west to Nanterre Université, a little over half an hour. Located near what is now called Paris Nanterre University (formerly Paris X Nanterre), the area is filled with undergraduates hurrying to their classes.

Registering for a reading room card was straightforward enough, though initially I had some confusion navigating their website. Sending an email through the website inquiring about a card received a prompt reply. Once I was able to set up an account, I navigated the catalog and identified potential sources to request. Unfortunately, a good amount of the material I wanted to view had been lost and was therefore unavailable to consult. What I did find, however, proved to be useful for my research.

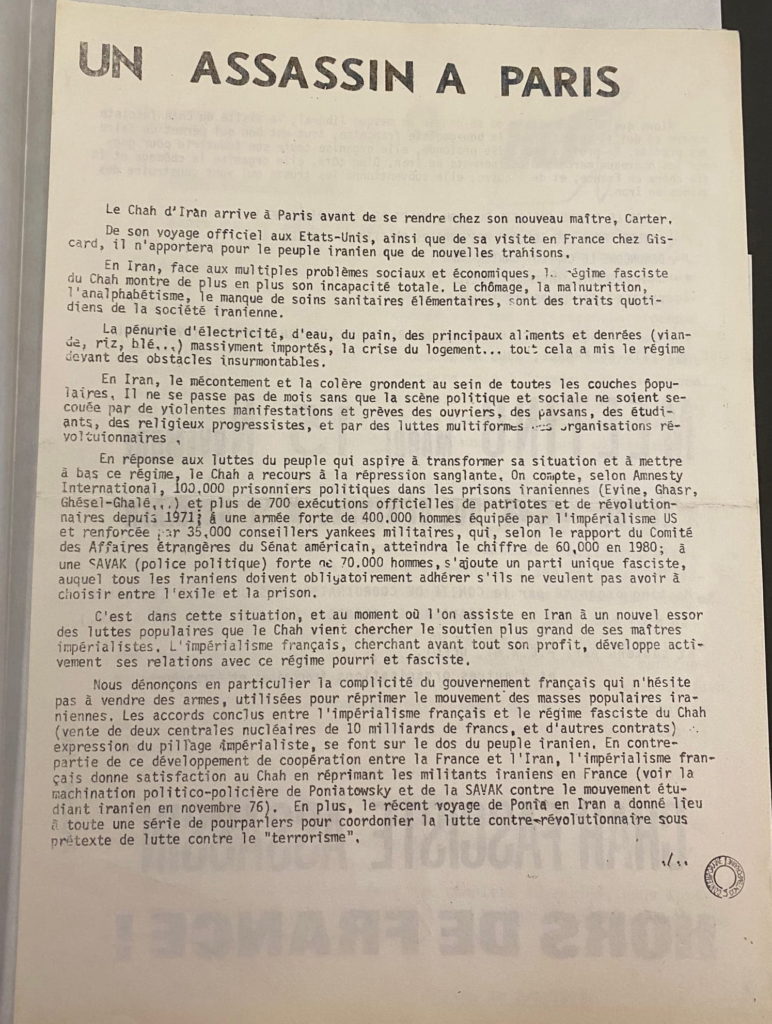

The Shah of Iran visited France in November 1977 and claimed that Iran was prepared to “place new industrial orders in France worth billions of dollars.” The UEIF prepared a protest meeting on Tuesday, 15 November at 8:30 PM at 44 rue de Rennes in the 6th arrondissement. The pamphlet produced for the meeting announced on the recto, “Un assassin à Paris” while the verso proclaimed “Chah fasciste assassin / Hors de France !”

In Susan Howe’s Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives, the author writes, “For conversion, there must be a mysterious leap of love. Sometimes, a hidden verso side acts as a prior counterpoint. The way improvised children’s tales have needlepoint roots in Latin holy words and medieval jargon. What difference does it make if what we see before our mind’s eye has already been interpreted? This meanly magnificent ‘waste’ exists on a scale beyond actual use. It provides us with a literal and mythical sense of life hereafter….” (25).

The organizers wrote that they “denounce the complicity of the French government which does not hesitate to sell arms, used to suppress the movement of the Iranian popular masses.” And, “While Giscard tries to put on a liberal mask, the visit of the fascist Shah shows what it is all about. For the French bourgeoisie, everything is good that allows them to make profits. In the grip of a deep crisis, it organizes all its industry to win the new markets of equipment in Iran.”

I wondered to myself, thinking through Howe’s provocation to consider the temporality of textual interpretation, if the vision of the shah invoked by the UEIF advertisement conjured up spectral memories of authoritarian despotism in Iranian history for its readers? How did revisionist, New Left conceptions of economic inequality converge with the embodied practice of Iranian student activism in Paris? Looking toward the document’s textuality, I asked myself what histories of displacement, what series of events — changing of hands — created the conditions of possibility under which these documents found themselves at La contemporaine?

The ephemera produced by French Iranian student movements available at La contemporaine, in addition to a veritable panoply of documents concerning student movements in general, allows us to investigate a cosmos of traces (and their fragments). Through this “magnificent [archival] waste,” we can begin a project of recovering the heartbeat of student activism through the margins and marginalia of intellectual and cultural production.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Heydari is a historian of twentieth-century Europe. He focuses on French cultural, intellectual, and migration history. His current research project focuses on the out-migration of Iranians (especially students, intellectuals, and cultural leaders) from Tehran to Paris before and after the 1953 coup d’état.

Thank you very much for this, Keanu!