When it comes to the images that Olympic organisers seek to portray, there are several familiar discourses that emerge.

These concern notions such as the supposed unifying potential of sport and the idea that it can contribute towards achieving peace.

Within the official programme of this year’s Summer Olympics and Paralympics, the Paris 2024 organisers follow a familiar approach at the same time as mapping out some notable Olympic firsts. These include the French capital playing host to the first ever opening ceremony to take place in the heart of the host city rather than within a major stadium. In addition, the guide makes much of the games being the first to see equal numbers of female and male athletes. It also returns to themes of inclusion and participation by mentioning the fact that over 40,000 members of the public will be able to run the Olympic Marathon route during the Games.

Within official discourses concerning the Olympics – and indeed some media reporting – there is at times a tendency towards celebrating the history of the games without adequately assessing their contradictions or the challenges that they face. Pierre de Coubertin is widely celebrated as the fonder of the Modern Olympics, often in a way that largely obscures ways in which his approach to the Games – and sport more broadly – could be considered both elitist and sexist.

In May of this year, France 2 broadcast a documentary presented by Stéphane Bern that was entitled Pierre de Coubertin: grandeur et mystères du père des J.O. The programme’s references to perceptions of de Coubertin as being elitist and sexist became somewhat obscured as Bern’s long-standing fascination with nobility and royalty resulted in such issues largely being swept under the carpet.

The founding principle that participation in the Olympics was to be restricted to amateur athletes might initially seem like a positive means of celebrating a vision of sport based on the pursuit of glory and excellence rather than financial gain. However, the paradox of this approach is that it helped to make Olympic competition something of a middle class preserve as it was a lot easier for those in reasonably well remunerated jobs to refuse payment linked to their sporting pursuits.

For much of the 20th century, leading figures in the International Olympic Committee did not have particularly progressive attitudes to the participation of women in sport. Pierre de Coubertin notably made the following statement in 1912:

This use of the word ‘incorrect’ has been a focus of several recent initiatives that have sought to tell the story of women’s participation in sport and their battles against discrimination. These include a sports-themed walking tour of Paris by the collective Feminists in the City which was is called Les Incorrectes du sport, as well as a documentary film by Anne-Cécile Genre entitled Les Incorrectes: Alice Milliat et les débuts du sport au féminin.

Alice Milliat was born Alice Million in Nantes in 1884. She was a founder of several clubs and organisations that aimed to promote women’s sport and a keen participant in sports such as swimming and rowing. Milliat was one of the founders of the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale and lobbied for women’s athletics events to be included in the 1924 Paris Olympics. There is now a statue of Alice Milliat near one of Pierre de Coubertin in the headquarters of the French Olympic Committee. Milliat also receives a brief mention in this year’s official programme of the Paris 2024 games and has been the subject of several books published during recent years in both French and English.

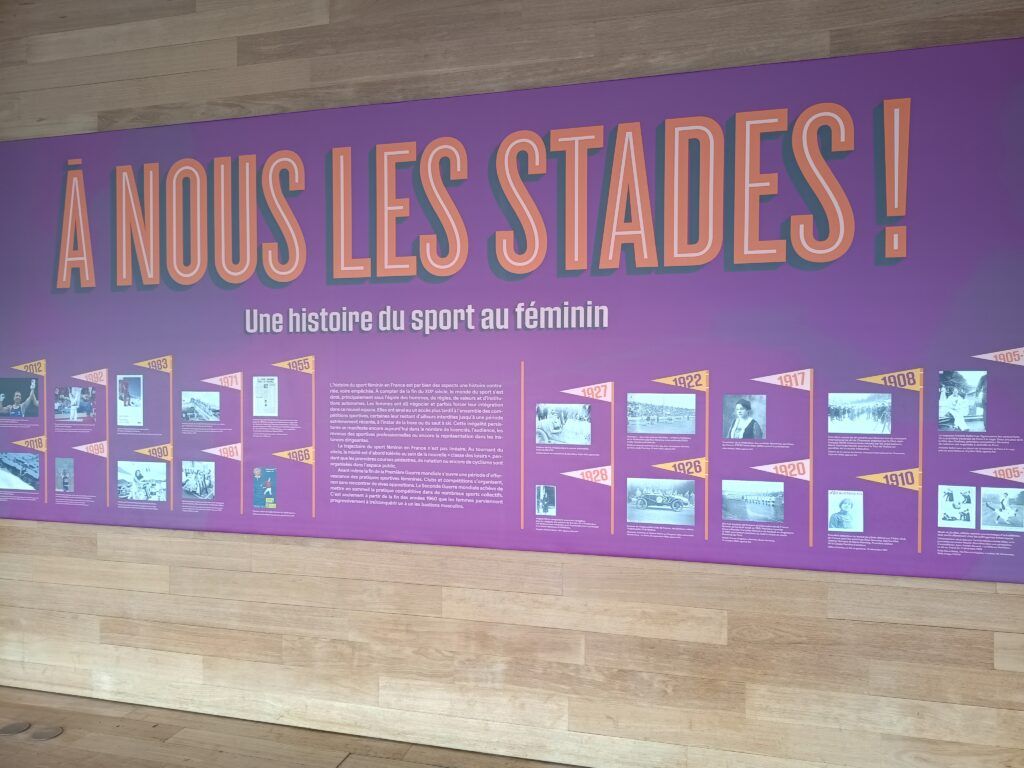

Milliat’s work is celebrated by the Fondation Alice Milliat, which continues to lobby for better representation of female athletes as well as gender equality in sport. Alice Milliat is also a person whose lobbying in favour of women’s sport – and the opposition she faced from the French and international sporting establishment – is mentioned in several exhibitions about sport which are currently on show in Paris. These include Olympisme, une histoire du monde at the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration and À nous les stades ! Une histoire du sport féminin at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (François Mitterrand site). Milliat’s contribution to French and international sport was also discussed at the recent Faites du sport exhibition at the Archives départementales du Val-de-Marne in Créteil.

Museums in Paris and the surrounding area are finding a variety of ways to examine sport in local, national, and international contexts. One particularly intriguing and creative approach can be found in the exhibition Marathon, la course du messager at the Musée de la poste. The starting point for this exhibition is the origin of the marathon as a race commemorating a quest to deliver a message, and thus fulfil a role similar to that of the postal service. Although to some this may sound somewhat contrived, the exhibition weaves a fascinating trail through ancient history, running as a pastime and sport, as well as cinematic and literary representations of running. The Musée de l’histoire vivante. In Montreuil is currently hosting an exhibition entitled Sport en banlieue parisienne, which explores the socio-cultural importance of sport in these areas.

The Olmypiade Culturelle which accompanies this year’s Olympics and Paralympics has already featured quite an eclectic range of events that invite reflection on the power of sport as well as its cultural representation. These have included Mohamed El Khatib’s play Stadium, which explores what it means to be a football fan. In Plusieurs, the actor Bertrand Bossard delivered a monologue – which he also co-authored – to a horse named Akira who was also present on stage. Orchestre Divertimento, conduceted by Zahia Ziouani, has performed Rhapsodie sportive in several locations in the Paris area and elsewhere in France. It has involved the orchestra seeking to ‘create bridges between symphonic music and sport’ via a show that combines classical music, breakdance, and BMX.

When the legacy of Paris 2024 is assessed in years to come, it will be fascinating to see what impact the games will end up having on discourses surrounding sport and participation, relations between sport and academia, as well as broader relations between sport and culture.

Dr. Jonathan Ervine is a Senior Lecturer in French and Francophone Studies at Bangor University where he is also Head of Modern Languages. He is currently writing a book about contemporary French sports films and has published on aspects of French sport such as football and national identity, sport and the media, and sports videogames.