Dr Daniel Gordon is Senior Lecturer in European History at Edge Hill University, and the views expressed here are his own.

So, if France’s capitalists have been known to have a soft spot for Russia, what about its communists? Once upon a time, this would have been a question with an obvious answer. Previous Communist Party leaders Maurice Thorez supported the invasion of Hungary in 1956, and Georges Marchais the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 – the kind of thing that in 1980 inspired the popular, formerly Communist-fellow-travelling singer Jean Ferrat to pen a song to denounce Marchais’ comments that the Soviet Union had a ‘globally positive balance sheet’ [Link to Jean Ferrat – Le bilan – Live Stéréo 1980 – YouTube], only to still vote for him come the 1981 election. Today, though, the answer is more nuanced.

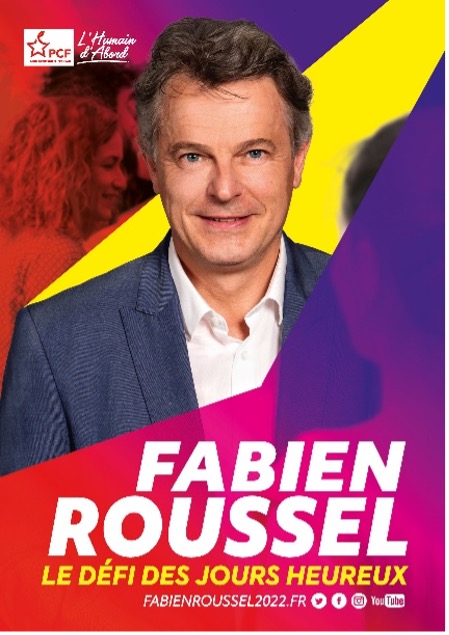

It would be deeply ironic if the only thing that prevented a hard-Left candidate from reaching the second ballot, for the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic, was the decision of the Communists, long fed up with being Mélenchon’s bag-carriers, to fly solo for this election. This is the first time in 15 years that there has been a Communist presidential candidate, and the first time in 20 years that I have seen one in action. Yet Fabien Roussel, even as his vote gets squeezed by Mélenchon as polling day approaches, has already made more impact than his predecessors Robert Hue in 2002 and Marie-George Buffet in 2007 put together, or indeed his Socialist opponent Hidalgo in 2022, thereby achieving the principal aim of those first ballot candidates who know they are not going to be elected President: to show the public that they (still) exist, and are more dynamic than rivals in the same half of the political spectrum.

While I have attended many amateurishly organised leftie events in my time, Roussel’s rally in Bordeaux on 1 March was anything but. It more than filled Le Pin Galant, a 1400-capacity theatre in Mérignac, a suburb known for its aviation industry, plus overspill screens outside for what organisers claimed was a total turnout of 3000. Roussel’s rally was certainly slicker and more modern in style than Hue’s in Nice in 2002. It could be paradoxically caracterised as a professional production of authenticity – from the very hi-tech audiovisuals to the youthful mixed-gender pair of hosts warming up, in the manner of a Saturday night TV show, crowds bussed in from right across southwestern France (‘Who’s here from Charente-Maritime? … Have we forgotten Lot-et-Garonne?’). Despite the red flags fluttered by enthusiastic supporters and later clutched by them on the tram replacement bus service back into Bordeaux, the word ‘communism’ barely passed the lips of Roussel, who instead presented himself as the candidate of a campaign for, in the words of his key slogan, La France des jours heureux.

To a historically literate French audience, Les jours heureux is a straight reference to the programme of the Conseil National de la Résistance, signed on 15 March 1944, at which all political parties agreed on an ambitious programme of social and economic change for postwar France. It thus conjures up a promising moment of change, when Communists worked together with non-Communists to renew French society. While Roussel was born a quarter of a century later, his parents were Communists and he was literally named after the famous Communist Resistance martyr ‘Colonel Fabien’, who in August 1941 (whilst Operation Barbarossa raged around Kiev), shot dead a German officer as he boarded a metro train, in what has gone down in history as the first act of armed resistance in occupied Paris.

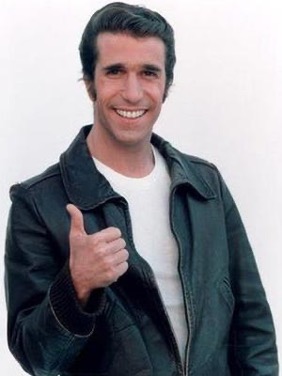

By contrast, Anglo-Saxon ears might think of Happy Days, the highly popular 1970s/80s sitcom-with-canned-laughter about a gang of 1950s Milwaukee teenagers led by the charismatic leather-jacketed biker known as ‘The Fonz’. Happy Days was actually shown on French TV, so it is possible that Roussel is aware of the potential double meaning, though given that the young Roussel’s father was Vietnam correspondent for L’Humanité, it would have been at odds with his milieu to have been a fan at the time of such an icon of American cultural imperialism as ‘The Fonz’ (apparently an Eisenhower supporter).

But in both Roussel’s La France des jours heureux and Happy Days, the implicit meaning is of nostalgia for the world’s post-war, pre-oil crisis boom as a (supposedly) carefree time of plenty for the masses. In the former case the added nostalgia is for a time which was the all-time height of the Communists’ electoral popularity. It seems a fitting coincidence that, alongside Roussel, other attractions at Le Pin Galant this season include a performance by that popular icon of the end of the Trente glorieuses, Jane Birkin.

It might thus not be too outlandish to suggest Roussel is positioning himself as the ‘Fonz’ of the French Left – seeking to reprise the lost age when there was such a thing as a gauche populaire, in a choreographed manner forward-looking enough, and grounded enough in the classic theme of equality, to attract left activists disenchanted by Mélenchon’s posturing, yet sufficiently nostalgic and culturally conservative to appeal to some blue-collar voters who do not recognize themselves in the identity politics embraced elsewhere on the Left. Just as the original ‘Fonz’ was both a rebel and a ’good guy’, who sought to be a force for positive change in his local community while ultimately conforming to dominant codes of honour and masculinity, so Roussel seeks to reconcile a progressive agenda with an appeal to hegemonic French working-class morality.

Inevitably the meeting concluded with the Communist Party’s time-honoured sequence of Marseillaise followed by fists-raised Internationale, but these were immediately followed by up-tempo rave music. In a country with good claim to be the world champions of pessimism, the upbeat vibes and bright rainbow-coloured positivity of Roussel’s campaign is a bold choice. Roussel is (ironically, rather like Macron) an optimist in a country of pessimists. In an age of resentment and negativity, he has chosen instead to fight a more positive campaign. Roussel’s uplifting, even futuristic, nostalgia could hardly be further in tone from the bitter, racialised nostalgia of Zemmour or Le Pen. But in his Mérignac speech, Roussel neither mentioned any of his opponents by name, not even the sitting President, nor did he talk about himself. Instead, as we shall see, Roussel did something still relatively unusual for a male politician – something probably neither the ‘Fonz’, nor Roussel’s predecessor-but-four Georges Marchais, would have done: he spent most of his speech talking about gender equality.

In some alternative universe where happiness did not feel inappropriate at a time when, as the Bulgarian intellectual Ivan Krastev puts it, ‘We used to be in a postwar world, now we are in a prewar world’ – and in a universe where Mélenchon did not exist – Jours heureux might indeed have been ahead for Roussel, given the extreme weakness of other forces on the Left such as the Socialists. But in this universe, circumstances obliged Roussel to start by saying something about the decidedly unhappy situation in Ukraine, expressing solidarity with the people of Ukraine and the democratic opposition in Russia. Cynics might suggest that Roussel was protesting too much his unreserved condemnation of Putin (‘Our condemnation is total!’) in order to compensate for the apparent ‘both sides-ism’ of his earlier pronouncements in favour of French withdrawal from NATO, and respond to attempts by rivals such as Jadot of the Greens to draw a dividing line on Ukraine.

Still, this was a far cry from Thorez or Marchais. The first thing Roussel’s audience were shown while waiting for the meeting to start was a video of him speaking in the National Assembly that afternoon firmly denouncing Putin’s aggression. But the emphasis on peace at the start of Roussel’s Mérignac speech, warning of the dangers of world war, reprised a classic theme of Communist rhetoric. The audience was enjoined to join Roussel in chanting ‘Stop à la guerre!’, and shown pacifist quotations from the likes of Paul Vaillant-Couturier, the writer and founder member of the Party and of a fellow-travelling association of antimilitarist First World War veterans. Another late addition: whereas last year, Roussel faced criticism on the Left for opposing an open door immigration policy, in the context of a new refugee crisis in Europe, Roussel seized the moment, in a rare populist flourish, to demand the requisition of Russian oligarchs’ villas in France to house Ukrainian refugees. Within a couple of weeks, activists would be taking such matters into their own hands in France as elsewhere, occupying a villa in Biarritz owned by Putin’s ex-son-in-law, and Roussel’s suggestion would seemingly become British Conservative Party policy.

But the main prepared theme of Roussel’s Mérignac meeting, timed for the run-up to International Women’s Day, was what Roussel’s manifesto proposes as a ‘feminist revolution’. The candidate’s speech was preceded by contributions from two French feminist activists, and a pre-recorded video by an MEP from Unidos Podemos (the Spanish equivalent of the now defunct alliance between the Communists and Mélenchon) about what they have achieved for gender equality in a coalition government to the south of the Pyrenees. This contribution enabled the meetings’ hosts to press another button dear to Communist hearts, internationalism, by claiming a resonance of Roussel’s campaign beyond the borders of France (‘There’s even been an article about our campaign in the New York Post!’).

The key buzzword of Roussel’s speech, though, was ‘equality’, and the bulk of it was devoted to, first, Roussel’s promise of a billion euros to fight against what he referred to as ‘sexual and sexist violence’, through a combination of policing resources and anti-sexist education from an early age to instill gender equality as the social norm; and secondly, the need to tackle the gender pay gap which persists in France despite 14 laws passed to combat it since the early 1980s – by increasing the salaries of mainly female professions such as care workers. Almost the only individual singled out for criticism was an unnamed professor at Sciences Po Paris, on whom Roussel poured scorn for arguing that this would cost too much. Both these manifesto pledges are presumably calculated to enable Roussel to speak simultaneously to what remains of the core Communist vote and a wider electorate including, as he explicitly stated in his speech, voters without partisan attachments who may have previously voted for the Right or even extreme Right. Introducing the theme of security through a feminist angle might enable Roussel to perform the tightrope walk between speaking to floating voters on the terrain of law and order traditionally occupied by the Right and accusations from the Left that he is some kind of reactionary crypto-fascist for wanting to address security at all. Much of what Roussel is proposing, though, is hardly unique: the pledge of a billion euros to fight sexual violence has also been made by Hidalgo, Jadot and Mélenchon, repeating a demand from feminist activists, critical of the way that in 2017 Macron jumped onto the MeToo bandwagon by declaring this a ‘grande cause nationale’ but then failed to increase funding sufficiently.

But speakers at Roussel’s rally claimed that the Communists are unique on the French Left in advocating an abolitionist position on prostitution, which he justified in terms of a wider universalist and anti-capitalist principle that ‘the human body is not for sale’, thus for example paid-for surrogacy should also be illegal. Approaching gender equality through the prism of economic inequality might enable Roussel’s call for a ‘République sociale et démocratique, laïque et universaliste, écologiste et féministe’ to be heard beyond the limited sociological base of today’s bac+8 Left. As befits the deputy for the 20ème circonscription du Nord, a constituency in France’s far north bordering Belgium, Roussel’s is, in theory, a decidedly blue-collar feminism, returning to the bread-and-butter basics of higher wages for the low-paid female workers who he identifies as ‘the proletariat of the 21st century’. Nevertheless a clue to the identity of the audience which, though some younger people were present, was clearly older than the young people placed sitting casually on stage as a backdrop to Roussel, and whiter than the passengers on the average Bordeaux tram, was that the loudest cheers came for Roussel’s promise to increase public sector salaries; even his dig at the Sciences Po professor was supplemented with a nod of apology to any professeurs present. A lot of modern leftism is public sector employees trying to out-left each other, in an illustration of the narcissism of small differences.

The issues at stake, though, can be deadly serious. Roussel is positioning himself as a feminist in a manner which, while not exactly new in the history of Communism – as historians such as Kristen Ghodsee and Celia Donert have argued, women’s rights became prominent in Eastern European state socialist discourse in the 1970s and 1980s – and framed in a classic republican language of universalism and equality, is contemporary in its resonances, especially on gender-based violence. Another of the loudest cheers was heard when Roussel invoked the memory of Chahinez Daoud, a 31 year old Algerian mother of three living in Mérignac, burnt alive by her ex-husband in one of 113 femicides in France last year. Among the shocking facts of Daoud’s case (not spelled out at the meeting, perhaps because they don’t all easily fit within Roussel’s security framing) are that Daoud’s killer had been released from prison after seven previous convictions for violent offences, and the police officer who took a statement from Daoud at the local police station two months before her murder had only a month beforehand himself been given a suspended prison sentence for domestic violence.

The apparent sincerity of Roussel’s feminist discourse was arguably in tension with the implicit message sent by the hierarchy of speakers, where four women spoke, but all as a prelude to the perceived main event of the male candidate’s speech. More generally, with the obvious exception of Le Pen, women’s voices have mostly, once again been marginal to a presidential process still shaped by ‘republican monarchy’ and De Gaulle’s gendered notion of a quasi-mystical encounter between one man and the French people. It says something about the implicit boundaries of power that Christiane Taubira – the only Black woman ever to stand for President and a former Justice Minister responsible for two historic achievements of the French Left, the law recognising slavery as a crime against humanity and the law on equal marriage – could not even get the 500 signatories from elected officials to stand – let alone convince Mélenchon, Jadot or Hidalgo to accept the result of the Primaire populaire in which Taubira outpolled all of them in January. Supposed to produce a united candidate of the Left, the Primaire populaire could not get the principal parties even to agree to participate.

Other longstanding tensions within Communist policy were evident at Roussel’s meeting. They are for environmental protection, but in favour of nuclear power: Roussel’s visuals included an apparently happy combination of solar panels and nuclear power station as solutions to the climate crisis. They are for public transport, but also for the car industry. Again the visuals at Mérignac featured happy images of cars and buses alike. These enticingly utopian visuals promised both free public transport (my own current research area) and also free driving licences for the under-25s, which would surely cancel each other out as far as any ecological benefit of the former is concerned. Thus Roussel is proferring what André Gorz, writing nearly half a century ago called ‘the social ideology of the motor car’ – a kind of demagogy where the Left, which at the time largely meant the Communists, pretends that it is possible for everyone to have access to the freedom to drive where they want, when they want. As an East German friend of Gorz put it on witnessing the notoriously selfish manner in which Parisians drove, ‘You’ll never have socialism with that kind of people’.

Also striking is the symbolic role that food has played in Roussel’s attempts to enlarge his audience beyond the Communist faithful. In January, he created a storm in the teacup that is Twitter, by telling TV viewers that ‘Un bon vin, une bonne viande, un bon fromage, pour moi c’est la gastronomie française … mais pour y avoir accès, il faut avoir des moyens, et donc le meilleur moyen de défendre le bon vin, la bonne gastronomie, c’est de permettre aux Français d’y avoir accès. Et je dis que le bon, le beau, tout le monde doit y avoir accès’. A few years ago, indeed in much of France still today, the first clause would have been an uncontroversial statement of the bleeding obvious. Yet critics honed in on it, misreading the reference to wine as a racist dog whistle intended to exclude Muslims, and denouncing the reference to steak as ecologically incorrect. In reality Roussel’s main point lay in the latter part of the statement, calling for pay rises, and upholding an honorable tradition on the French Left, that decent food and beautiful things should be democratically accessible to all, and the masses not palmed off with rubbish (remember when José Bové dismantled a McDonalds?). This is a vision with which environmentally-friendly measures such as eating meat less often, but of higher quality, would be compatible. Insofar as Roussel has sought to engage in the culture wars, his target is not ethnic minorities, but that puritanical wing of the Left which, for Roussel, wants to make ordinary people feel guilty for enjoying life’s simple pleasures, and then wonders why it lacks popular support.

Roussel riposted to his critics with references to ‘la gauche caviar et quinoa’. La gauche caviar is now an old trope, used against Mitterrand’s supporters in the 1980s, equivalent to the English ‘Champagne Socialist’, with the Russianness of caviar and the Frenchness of Champagne playing a role in positioning cultural elites as suspiciously foreign in their expensive tastes. La gauche quinoa, however, is new, with quinoa taking a class significance equivalent to avocadoes or latte in modern Anglo-Saxon culture war discourses. Although Roussel’s most obvious targets here might be Hidalgo or Jadot, perhaps this was also a coded dig at Mélenchon, who revealed to a celebrity magazine in 2016 that his secret recipe for slimming is – wait for it – quinoa salad.

In the closing weeks of the campaign, Roussel’s last throws of the dice include encouraging his supporters to invite their friends to convivial 6 o’clock apéros to talk about his policies – while making it clear that options both with and without wine, and with and without pork, should be available. Then on 25 March Roussel broke the traditional, if now rather lapsed, French rule that politicians keep their private life strictly private, by revealing that his stepson is the professional Mixed Martial Arts fighter Kevin Oumar. Roussel thus knows how to play the rules of the capitalist game, garnering publicity in such well-known Marxist publications as Closer magazine. While the ostensible purpose was to highlight his policies to encourage popular participation in sport (which the last time that Communists served in government was one of their portfolios), the unspoken part of this announcement, that Oumar is Black, might constitute a further inflection of Roussel’s positioning in the culture wars.

A hint of the historic links between France and both Russia and Ukraine was recently given by the death of Alain Krivine, who in 1969 invented the tradition of extreme left candidates at a Fifth Republic presidential election. This tradition survives him: Krivine’s current, once the Ligue communiste révolutionnaire, now the Nouveau parti anti-capitaliste, is represented in the current election by the redundant car worker and Bordeaux city councillor Philippe Poutou. Sectarian division being an even more ancient and venerable tradition on the French Left, no presidential first ballot is complete without at least two Trotskyists, so as usual Lutte ouvrière, for whom Trotsky represents an even more fundamental political reference, are also standing, represented by economics teacher Nathalie Arthaud. The ongoing legitimacy in wider French political culture of currents ultimately deriving their political perspective and iconography from a certain famous Russian-Jewish revolutionary from Ukraine was suggested by the bearing of a wreath at Krivine’s funeral by Mélenchon, whose formative years were spent in yet another Trotskyist faction. Mélenchon’s training in Trotskyism has come in handy recently, as he can point out that he is old enough to have opposed (as a lycée student activist) the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Tributes to Krivine, whether by his comrades on the far left, or by, of all people, Macron – incongrouously given that Krivine spent his life struggling against most of the things that Macron stands for – invariably describe Krivine family as ‘Ukrainian Jews’. While this term is true to Krivine’s own self-identification in his autobiography Ca te passera avec l’âge, its usage today is no doubt influenced by the present context. As Krivine’s entry in the Maitron dictionary of labour biography indicates, his father’s parents were born in what is now western Ukraine, though his mother’s parents in France and in a part of Romania then in the Austro-Hungarian empire. However given the ethno-religious-linguistic categorisations of the time, wouldn’t Krivine’s paternal grandparents have been labelled by the Tsarist state as Jewish, not Ukrainian? For these were then seen as mutually exclusive categories: in 1927, one of the most important anti-racist organisations in France was founded to defend the Jewish anarchist assassin of a Ukrainian nationalist leader accused of complicity in pogroms. On arrival in France, wouldn’t the Krivines have been perceived as ‘Russian Jews’? More than twenty years ago, I was granted a dérogation to see the French police’s ‘foreign agitator’ file for May 1968, and while Krivine did feature in it – wrongly given that Krivine and indeed both his parents were born in France – I do not recall the word ‘Ukrainian’ appearing in the description given of his Romanian and Russian family links. Identity can be complicated: at the time my own Yiddish- and Russian- speaking family, with roots in Kazakhstan and among the Crimean Tatars, left Odessa, Ukrainians made up only a small minority in a mainly Russian and Jewish city with very diverse international influences. Even when I visited a century later, Russian was in practice still the lingua franca of Odessa: a bit like the use of French in Algeria, it is ultimately a product of imperialism, but cannot be reduced to it, or abolished overnight by state fiat. In the current climate in the West, it seems, to update the slogan coined in 1968 for Krivine’s fellow student leader Dany Cohn-Bendit, that ‘we are all Ukrainian Jews’. Yet it would be anachronistic to retrospectively apply the recent evolution of Ukrainianness into a more inclusive civic identity so as to present myself as Ukrainian.

French political vocabulary is still littered with concepts borrowed from Russian history. In April 2021, when Roussel criticised Mélenchon’s promise of a jobs guarantee, ie advocating the state as employer of last resort, interestingly Roussel did so by claiming that ‘Nous ne partageons pas du tout cette philosophie là, ça c’est l’époque soviétique, le kolkhoze’. The historic irony of the leader of the French Communist Party accusing a rival of advocating Soviet-style collective farms was not lost on Roussel’s critics on the far Left (see for example “…ça c’est l’époque soviétique, le kolkhoze.” – NBH-pour-un-nouveau-bloc-historique.over-blog.com or Fabien Roussel, Don Quichotte d’un communisme introuvable – CONTRETEMPS]). More recently, when Zemmour sought to hoover up the votes of motorists angered at fuel price rises (presumably without drawing attention to the link between these and the actions of Putin) by appearing at a petrol station in the Tarn-et-Garonne to speak to what were presented as random members of the public, but turned out instead to be his planted supporters, Zemmour was accused of creating a ‘Potemkin village’ – an accusation also previously made by Zemmour himself against Macron.

So what does all this mean for the outcome of the election? While it would be fair for Macron to say it was not his fault that Putin decided to start a war in the midst of a French election, he has certainly made the most of the advantages it affords him, haughtily refusing to debate with his opponents before the first ballot. ‘Jupiter’ surely has more important things to do, like lead the world, than waste his time talking to ‘people who are nothing’ like that unemployed layabout Poutou, who could just ‘cross the street to find work’. (I exaggerate, but only slightly – those are real quotations from Macron in other contexts). The idiosyncrasies of Fifth Republic two-ballot presidentialism mean that he could maintain power despite what the historian Marc Lazar calls the ‘transversal hatred of Macron’, transversal in that there are millions of people who utterly loathe the man, among the working class and on Left and Right alike – a combination not equalled by any recent President. All Macron has to do is maintain for the first ballot the support of the most comfortable quarter of the electorate, then at the second ballot perform the hardly Herculean feat of being slightly less unpopular than Marine Le Pen, and his path to a second term is apparently clear.

Ironically, two of the few countries in Europe that, like France, have theoretically semi-presidential systems of powerful elected president, plus prime minister with some degree of accountability to parliament, are Ukraine and Russia. Yet Macron is planning to make France’s presidentialism even stronger, by implementing if re-elected his plan, previously blocked by the Senate, to reduce the number of Deputies and Senators and the number of terms they can serve, and hence the capacity of the National Assembly to hold the executive to account. He is like some California ‘tech bro’ – younger and cooler than your old boss, but more authoritarian. As Sarkozy put it: ‘me, but better’.

However, the constant repetition by all and sundry of the inevitability of Macron’s triumph does make me wonder – perhaps because I can remember 2002, when ‘everyone knew’ that Lionel Jospin would face Jacques Chirac at the second ballot, only for everyone to be proven wrong – how many people will actually bother to turn up to vote for this supposedly preordained outcome. Traditionally French presidential elections have a high turnout, but given how massive has been abstention in recent second-order elections, and how unusual the current campaign has been, it seems rash to assume this tradition is bound to continue. In particular, many leftwing voters do not want to get fooled again, like in 2002 or 2017, by voting for the Right to defend the Republic against the extreme Right and that being taken as a mandate for neoliberal policies. This is an argument which does leave the small matter of risking handing full power in a nuclear-armed state to a political force which has spent half a century trying to disguise its fascist origins, but is a plausible one to potential abstentionists.

Even if Macron does win, France has seen before how getting elected in such ‘better the devil you know…’ circumstances is scarcely a recipe for stable governance, let alone a convincing mandate for smashing what remains of the French social model. Given the repeated inability of La République En Marche! at the local elections of 2020, and the regional elections of 2021, which it lost in every single region, to establish itself as an actual political party, as opposed to an astroturfed fan-club, I would not place bets on a 2017-style En Marche landslide in June’s parliamentary elections. Yet so all-enveloping has become the crisis in Ukraine and its economic implications, that it has already been all but forgotten that most of Macron’s first term was characterized by a series of previous crises. First the state of emergency declared after the terrorist attacks of 2015 was theoretically lifted, but effectively made permanent by incorporating its provisions into common law; then there was the Benalla affair of 2018, when Macron’s deputy chief of staff was filmed beating up protesters and impersonating a police officer; then the gilets jaunes in 2018-2019; then the rapid climb up the political agenda of the climate crisis in 2018-2020, culminating in En Marche’s trouncing at the hands of the Greens in the prosperous cities which should have been favorable territory for Macron; and of course the Covid crisis. In the first ballot campaign, Macron is barely being held accountable for his (mis)management of previous crises, apart from the occasional call from Mélenchon for an amnesty for the gilets jaunes.

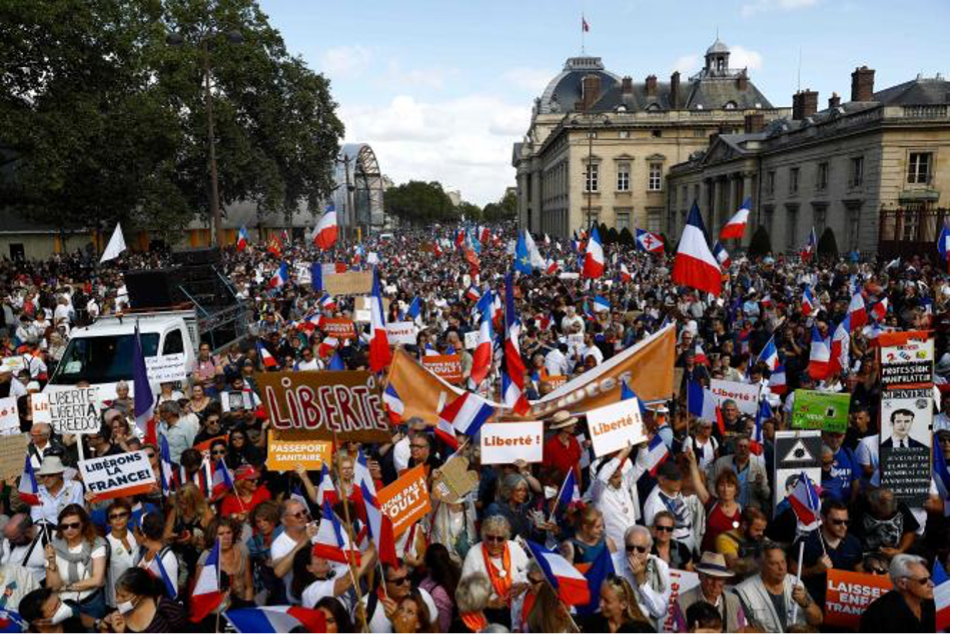

This is a problem, for Macron is the perfect representative of a managerial-technocratic class that thinks itself cleverer than and morally superior to everyone else, yet so rare to admit when it has messed things up. Take for example Macron’s highly politicised, but inconsistent, Covid authoritarianism: declaring ‘we are at war’ by ostentatiously locking down with the full resources of a Bonapartist police state in mid-March 2020, when the virus had been spreading in France since at least November 2019, yet not locking down in February 2021 in order to save the skiing industry; discouraging vaccine take-up at a crucial moment by trashing certain vaccines produced abroad, only to overcompensate by turning participation in everyday social life into a reward for vaccination, in defiance of basic principles of medical ethics; using the pandemic as an opportunity to attack civil liberties, as with the ‘Law on Global Security’ that sought to outlaw the filming of police officers, thereby criminalizing journalists and members of the public exposing police brutality; inciting hatred against the unvaccinated in deliberately offensive terms. Agnès Buzyn, Macron’s Health Minister at the start of the pandemic, and failed candidate for Mayor of Paris, was placed under police investigation for ‘endangering the lives of others’. Yet in typical technocratic fashion, critics of Macron’s Covid policies were dismissed as irrational extremists and conspiracy theorists (which, to be fair, some of them were), as a way of avoiding engaging with the substance of their arguments. Then finally on 3 March 2022, a week into the invasion of Ukraine, the passe vaccinal was quietly and cynically dropped, the very day before the last possible legal date for Macron to declare his candidacy. The President-candidate-turned-candidate-President was thereby relieved from having to defend a policy which had so clearly failed to prevent the spread of Covid – France’s pandemic death toll is actually, in spite of apparent divergences in political approach, grimly similar to that of basketcase Britain – but succeeded, like many of his other policies, in exacerbating France’s already glaring social divisions.

When I heard the announcement that from 14 March the passe vaccinal would be no more, I was on a lunch break from investigating the origins of one of the first free public transport schemes in France, in the municipal archives of the town of Provins, a medieval UNESCO World Heritage site now on the very furthest fringe of the Ile-de-France’s zone Navigo. Watching the TV news while eating a sandwich libanais with sauce algérienne in a Provins kebab shop was a privilege granted by a printout of my NHS Covid Pass, a document I would theoretically have been entitled to a whole year before (having been vaccinated early due to my clinically vulnerable status) but had only recently acquired for the specific purpose of going to France. Given the earlier quasi-impossibility of crossing the Channel during the prolonged period of post-Brexit tit-for-tat travel restrictions on the part of sometimes the French authorities, sometimes the UK ones, and a reluctance on principle – being broadly in favour of vaccines, but against passports – to enter the few venues in England which had required it, I was a latecomer to the party in honour of that great god of modern times, the QR code.

The next morning, in a café directly opposite the Rex cinema on the inaptly named Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle, outside which Algerian demonstrators were killed by police on 17 October 1961, I concluded my review for Modern and Contemporary France of a book about 17 October. Later that day, I visited an exhibition in the new building of La Contemporaine at Nanterre University about Elie Kagan, the photographer best known for exposing the massacre. Deserted on the afternoon of my visit, this intelligently curated exhibition deserves many more visitors. Finally, I headed to the Bibliothèque publique d’information in the Pompidou Centre, a great public institution (in spirit a little like the nearby branch of Flunch, with its legendary eat-as-many-vegetables-as-you-like buffet), which I have been using on and off since I was an 18 year old backpacker, being less sombre, elitist and user-unfriendly than, and open later than, the Bibliothèque nationale, inescapable though a visit to the latter is on any research trip to Paris. The sheer illogicality of the passe vaccinal was on display: since libraries were exempt, several hundred people could gather on each floor of the BPI with no pass demanded- with the sole exception of the library’s tiny café, open only to pass holders.

I had come to read Quand la Chine s’éveillera, a bestselling 1970s travelogue by the Gaullist intellectual and former Education Minister Alain Peyrefitte, in order to test the intriguing if unlikely sounding hypothesis suggested by one local newspaper cutting I had found in the Provins archives that Peyrefitte, then mayor of Provins, copied his free buses from Maoist China. Disappointingly, in his book on China Peyrefitte seemed to make no mention of free buses. However, in an eerie premonition of later events, Peyrefitte, an enthusiast for traditional Chinese medicine, did visit a hospital in Wuhan! A reminder, perhaps, that the destinies of what used to be called ‘the West’ and what they sometimes imagine to be their polar opposites in ‘the East’, are more intertwined than either would admit.