The SSFH Research Grant funds critical research for many early career historians. Here, Alexis Romano discusses how the SSFH grant allowed her to finalise her doctoral thesis, not least by adding oral history. An SSFH grant allowed me to travel to Paris two years ago for the final research trip for my PhD, undertaken at the Courtauld Institute of Art in the fields of art and dress history (2016). Entitled Prêt-à-porter, Paris and the Image of Women, 1945-1968, it addresses gaps in French history, notably concerning everyday French dress, and how fashion relates to postwar France, and women’s lives. Specifically, my research studies the development of the readymade clothing industry, and asks how it connected to France’s wider project of postwar modernisation and reconstruction, and to conceptions of national and gender identities, and modernity.

Through its relative accessibility, readymade dress (known as confection until the 1950s and subsequently prêt-à-porter) concerns a wide populace and collective notion of fashion. The industry underwent heightened growth during the period covered in my research, distinguishing itself from made-to-measure modes of dress production, such as haute couture. Therefore, shifts in its development reflect those in France’s construction of modernity during this twenty-five-year period, which was informed by transitions, into new economic and industrial systems, decolonised and urbanised landscapes, and by its perceived loss of political and cultural hegemony. Modernity also comprised contradictions, notably between modernisation and tradition, and prosperity and tension, felt by the individual in an increasingly standardised society and by women in their ambiguous status as French citizens, enfranchised from 1944. My research determines how women and professionals from the industry and government used fashion to negotiate the contradictions of modernity and identity in various ways.

Through its relative accessibility, readymade dress (known as confection until the 1950s and subsequently prêt-à-porter) concerns a wide populace and collective notion of fashion. The industry underwent heightened growth during the period covered in my research, distinguishing itself from made-to-measure modes of dress production, such as haute couture. Therefore, shifts in its development reflect those in France’s construction of modernity during this twenty-five-year period, which was informed by transitions, into new economic and industrial systems, decolonised and urbanised landscapes, and by its perceived loss of political and cultural hegemony. Modernity also comprised contradictions, notably between modernisation and tradition, and prosperity and tension, felt by the individual in an increasingly standardised society and by women in their ambiguous status as French citizens, enfranchised from 1944. My research determines how women and professionals from the industry and government used fashion to negotiate the contradictions of modernity and identity in various ways.

The thesis’ five chapters trace shifts in the above themes, and a transition from a modern to a postmodern narrative, from the immediate years following the Second World War and in the Fourth Republic in chapters two and three, to the first decade of the Fifth Republic in chapters four and five. The first chapter illustrates a main methodological focus of this research in its exploration of readymade dress, women, and Paris through the lens of the fashion media between 1945 and 1965, and interprets these three elements as constructions and as realities. In introducing an analytical mode to consider the symbolic production of fashion, as it is crystallised in image and text, the chapter facilitates the study of the ways readymade dress challenges or enters into that construction in the following sections, as it relates to women’s lives, national projects and technological and cultural changes. It establishes the centrality of the visual analysis of image and object to the overall research project, which is interpreted alongside history and period theory, including, for example, Henri Lefebvre’s writings on the everyday and Roland Barthes’ demystification project.

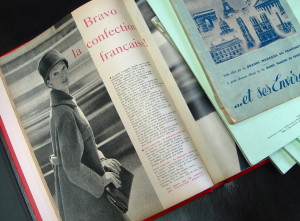

Through such cross analysis, my thesis seeks to decipher the construction of feminine identity as women increasingly consumed readymade dress through magazine reading or purchase. In an example from the 1 October 1956 issue of Elle, fashion editor Claude Brouet wrote: “Bravo la confection française! La partie est gagnée. Gagnée par les jeunes industrialistes du ‘Prêt à Porter’ qui ont sortie la confection française de sa routine.” The accompanying photograph by Lionel Kazan presented a model who wore a gray-brown wool coat by manufacturer Albert Lempereur. The model followed the speed and direction of modernity, evoked by blurred horizontal lines that represented the frenzied mass-populated city of Paris. With her legs cropped out of the photo frame, the reader could not tell if she was caught in mid-step, moving with the times, or caught off-guard, slowing down in fear. The image captured well the electric push to modernise both industry and city and presented fashion that would parallel it. However, in contrasting sharp focus, the model seemed to exist outside of modern time. Rather than resist its thrust, uncertain, she questioned the move forward. Her stance could be seen to reflect France’s contradictory reception of its abrupt postwar modernisation, which, as Kristin Ross noted, was ‘experienced for the most part as highly destructive, obliterating a well-developed artisanal culture.’ Prêt-à-porter, a product of the industry that perturbed mainstream notions of French artisanal production, was directly implicated in the country’s reconstruction. Articles in the fashion press, such as this one, which insisted on the success of French confection, thus sought to combat those views against modernity, but simultaneously laid bare a host of contradictions through their visual hesitancy and contrivance.

As seen above, Paris is the main spatial context in which my thesis analyses the representation of dressed bodies in imagery due to its position as the site of imagined consumption in fashion photography, as well as a main element in the symbolic construction of fashion. David Gilbert considers “the cities themselves as fashion objects, subject to fashion cycles, and visual accessories in fashion’s iconography.” In light of this concept, this thesis traces the changes in Paris’ visualisation alongside the continual reinvention of the industry’s own image, as well as shifts in conceptions of modernity and women’s lives. As readymade production became normalised in fashion imagery, depictions of the city shifted, and magazines borrowed and reappropriated older visual devices, such as the figure of la parisienne, as described by Agnès Rocamora in her study of the construction of Paris fashion in contemporary French fashion media. For example, while Kazan’s photograph is composed of the familiar parisienne figure, its depiction of Paris as an anonymous street with a blurred passing car differed from traditional literal renderings of Paris’ iconic spaces. This focus on the space of everyday Paris served to reposition fashion as informal and practical, as well as complicit in the construction of an active woman. Likewise, the blurred depiction of an automobile, achievable through new hand-held cameras, portrayed a rapidly changing fast-paced city, that was both exciting and daunting for the French, as described earlier by Ross.

My research project thus connects and juxtaposes diverse subjects in its goal to rethink French fashion and women’s history through the lens of readymade dress. To show the variety of players involved in the production and experience of fashion, it cross examines image with a wide range of sources, including surviving garments, industrial documentation and trade press, various contemporary commentary and my interviews of designers, journalists and manufacturers. The trip supported by the SSFH, which followed three years of research and writing, served to verify information as well as find new sources at institutions as varied as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Musée Galliera, Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Bibliothèque Forney, Archives Nationales, and Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, as well as in interviews with journalists and manufacturers, such as Ginette Sainderichin and Jean-Claude Weill. Finally, a defining feature of this trip was the opportunity to conduct oral histories with French women, in order to link object to memory, personal to macro history, and explore the experiential aspects of history through dress.

References

David Gilbert, “Urban Outfitting: The City and the Spaces of Fashion Culture” in Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church Gibson, eds., Fashion Cultures: Theories, Explorations and Analysis (London and New York: Routeledge, 2000).

Agnès Rocamora, Fashioning the Cit: Paris, Fashion and the Media (London: I. B. Tauris, 2009).

Kristen Ross, Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture (Cambridge, Mass. and London: The MIT Press, 1995).

—

To find out how you can apply for an SSFH Research Grant click here.

Alexis Romano is a historian of design and dress who completed her PhD in 2016 at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art. Prior to this she studied art and design history at the Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture (New York) and Université de Paris IV – Sorbonne. Her current research, to take the form of a manuscript and exhibition, stems from her doctoral thesis, which, titled, Prêt-à-porter, Paris and the Image of Women, 1945-1968, explores how the development of the readymade clothing industry connected to France’s project of postwar modernisation, conceptions of national identity, and women’s lives. In addition, Alexis is currently Exhibition Reviews Editor of Textile History and co-founder of the Fashion Research Network. Alexis Romano regularly blogs for the Courtauld Institute blog.

One Response

Dear,

How do I get a scholarship for research?

Thank