By Rebecca Scales, Associate Professor of History, Rochester Institute of Technology

My fall term began on Monday. I have no idea where the summer went, or frankly, the past sixteen months, as much of my teaching and research life has felt like a blur. My university shut down hastily during the spring holidays of 2020. Students who had returned home for the break were told not to return, and with the exception of students who had nowhere to go, the rest of the campus was told to pack up and leave. In that hasty move to online teaching, pedagogy took a backseat to the overall goal of just helping students finish the term and earn a grade. As spring moved into summer, my online writing group (composed principally of French historians) spent a good deal of time discussing how we would adapt our courses into fully online modalities, as well as the tools, resources, and techniques we could use. Not infrequently, though, I came up against a recurring problem: so many of these wonderful digital sources were not fully accessible for my students.

Accessibility is a priority at my university, the Rochester Institute of Technology, which is also home to the National Technical Institute for the Deaf. We have approximately 1000 Deaf/Hard of Hearing students and faculty on campus. They can request the supports of their choice for courses, from real-time captioning for live classes to ASL interpreting. If students request it, I will also wear a microphone. My university also has a captioning mandate – and after ten years of teaching here – I remain amazed at the number of academics I encounter who never really think about this issue. So many terrific online resources that colleagues pull for their students—from podcasts to videos—are not captioned or subtitled, which makes them completely unusable for me.

I am fortunate that RIT’s Teaching and Learning Services pays for professional captioning of video content – whether created by faculty (such as lecture videos) or web content (provided it doesn’t violate copyright). But requesting captioning through this service requires substantial advance planning. For a variety of reasons, last year I ended up having to self-caption my own lecture videos. While there are platforms such as Thisten and OtterAithat can live-caption zoom videos, I ended up storing my videos on youtube and editing them using youtube’s auto-generated captions. You can upload transcripts too, but this means you have to literally read a lecture word by word off a page – something I’m just not capable of doing). I’m no Luddite, but I found video creation to be an enormously time-consuming process. It took me approximately six hours to edit a lecture, record it, and caption it on youtube. If I had to do this again, I would find a better, more efficient strategy.

But the entire process of moving online was a useful reminder of several things:

- Captioning is not just for Deaf and hard of hearing students; it’s a service that’s useful for students with varied learning and comprehension styles. This is particularly the case if your lectures employ significant numbers of foreign words or proper names that students may be unfamiliar with.

- For years, ASL interpreters in my classes have noted that I speak quickly. I’ve tried to slow down, but being forced to caption myself brought home even more just how quickly I speak. It highlighted how students may have trouble taking comprehensive notes in my classes. Slowing down the pace is beneficial for all – especially when you’re online.

- Working with ASL interpreters and real-time captionists online presents a few challenges that don’t exist in a live class. Interpreters need to be co-hosts in zoom so that they have the power to spotlight themselves, allowing the students who use them to see both the instructor and the interpreter side-by-side. It also takes interpreters longer to find students who raise their hand to speak, so slowing down the pace of discussion is critical when online. But keeping the chat open also allows students who are reluctant to speak in class the opportunity for lower-stakes participation and intervention. I’m trying to think about ways I can incorporate this type of participation into in-person courses as I return to the classroom.

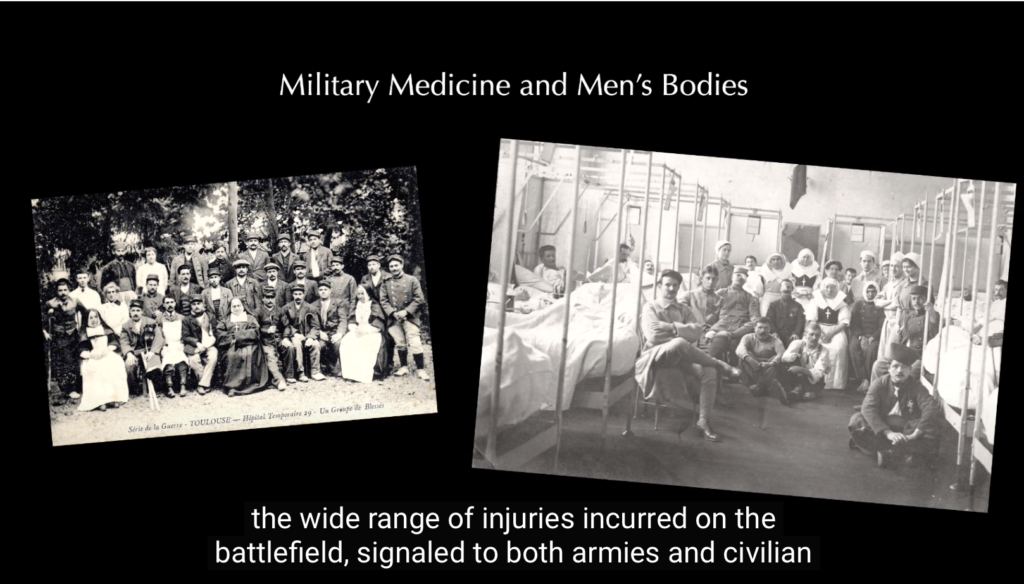

- Simplify, simplify, simplify. Condensing 50- or even 75-minute lectures into 30-minute videos helped me sharpen the focus of my lectures, even though I missed telling stories, discussing images, or trying to make my students laugh.

- I created weekly “engagement activities” that required students to use information from the video lecture to analyze a historical source. Designing these activities turned out to be quite entertaining (even if grading them weekly for 100+ students was not). Although these activities did not necessarily produce the kind of synthetic analysis I might wish to see on a final exam, they did make the course material digestible for short attention spans and require the students to engage critically with the lectures and readings. Ultimately, this work helped me find ways to integrate more critical thinking activities into my in-person courses this semester.

Pandemic teaching has also reminded me of the importance of simplifying syllabi and assignment instructions. When I first began teaching, over a decade ago, I tended to treat the syllabus as a contract that needed to contain every class or university policy. Some of us have more freedom than others when it comes to language that must be included on the syllabus, but we all know that students experience information overload.

For a few years, I’ve been using Accessible Syllabus (based at Tulane University) for guidance in simplifying syllabi and course handouts. I’ve restructured many syllabi to include images, pie charts, columns, and other graphic elements to highlight important details. Of course, it’s also critical to ensure that visually-impaired students can access these documents. This can mean providing alternative text for images (the site provides a helpful starting guide). But it can also mean using particular fonts or creating flexible texts that students can alter themselves.

Accessible Syllabus also includes helpful suggestions about reader-friendly font styles and text formatting that make it easier for students with ADD, dyslexia, or visual impairments to read more easily. Adobe Pro now contains a feature that allows you to check the accessibility of your pdfs – I did this once and was horrified by the document I had produced – so I went back and made more changes.

One thing I saw many colleagues do was embrace more accessible policies for accepting student work, as an acknowledgment of heightened student stress and possible illness during to the pandemic. For some, this meant abandoning firm deadlines or accepting late assignments with grade deduction. Although I kept assignment deadlines on my syllabi, I never turned down a single student request for an extension, and in some cases I granted the entire class a week or so of extra time when it became clear that they were exhausted and burned out. I also stopped taking attendance online, while making it clear to students that their participation was valued in every class. By and large, students who asked for extra time completed the assigned work. These types of policies, which some faculty appear very reluctant to grant, can make university more accessible for students with disabilities and chronic health problems.

As a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education observed, many students with disabilities who in the past found it difficult to obtain the learning accommodations they need often found it easier to study and learn during the pandemic. There are all sorts of reasons for this: faculty refused to take on the supposed “extra work” of making their courses accessible; universities were unwilling to spend on the technology necessary to ensure full accessibility; obtaining legally-mandated learning accommodations can be a complicated and lengthy bureaucratic process for disabled students; some students don’t want to make official requests for disability accommodations, and prefer to just get by.

If the pandemic eliminated some of these barriers, it also threw into relief the blatant hypocrisy of universities’ past refusals to accommodate disabled students. But as the sociologist Aimi Hamraie points out, “disabled people have been using online spaces to teach, organize, and disseminate knowledge since the internet was invented.” Not only should we as educators acknowledge this history and expertise, but we should be using this moment to think about incorporating lessons from pandemic pedagogy into our regular teaching practices. (Hamraie offers some terrific suggestions on her website, and her book Building Access is a must-read for anyone interested in the history of universal design, as well as the contemporary problems surrounding varied implementation).

This fall, I’ve returned to the classroom, but I also have one large online section of a popular film and history course. I’ve already implemented some of the changes I described above into my course preparation for the fall. But I’m also keenly aware of the ways my courses may still not fulfill all the “best practices” for accessibility. One of my goals for the next year is to begin building in alternate text for images into my power points and internal documents. I’m also hoping to see scholarly societies make questions of accessibility a priority. While debates about the future of in-person academic conferences and the pros and cons of online conferences have been the subject of fierce debate on academic twitter, few of these discussions have focused on questions of accessibility. As a community of scholars and teachers, I hope we can continue to push ourselves to do better.

Rebecca Scales is Associate Professor of History at Rochester Institute of Technology.